Writers on Writing #90: Chelsea Biondolillo

The Essayist Stutters, Stops, Starts, Goes

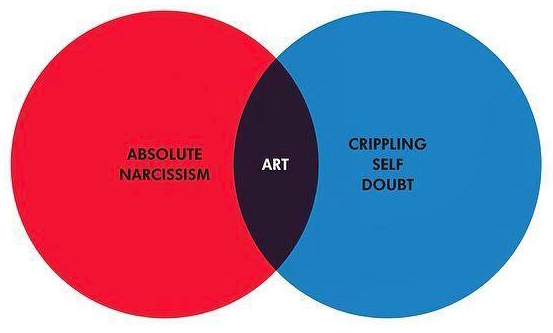

There’s an image making its round on social media of a Venn diagram with a circle labeled “Absolute Narcissism” and a circle labeled “Crippling Self-Doubt.” The area where they cross is labeled “ART.” (Note: I have searched for the source of this image, with no luck. If you made it, let me know.)

It’s making the rounds because a lot of artists and writers get it.

I get it.

As an essayist, I have to contend with these dueling voices in my mind that say on the one hand, “I must tell the world this amazing thought I just had!” and on the other, “Who the hell do you think you are, that they’d care?” But I don’t think those are the only voices that I need to write a good essay. There is a chorus of voices I hear when I sit down to write. And I don’t think my needs or experiences in this regard are unique. What I’m proposing, is that this diagram needs more circles.

***

The essayist must be over-sensitive—and not just emotionally, although essayists tend to feel deeply (see the remaining circles). They must be able to recall and recreate all five senses for a readership that has maybe never tasted an oyster stew (“mildly potent, quietly sustaining, warm as love and welcomer in winter” – MFK Fisher) or fresh white truffle (“like that of bird peppers or venison” – Gary Paul Nabhan); or heard a dawn chorus in fall in Wisconsin (“the invisible hermit thrush pouring silver chords from impenetrable shadows; the soaring crane trumpeting form behind a cloud; the prairie chicken booming from the mists of nowhere; the quail’s Ave Maria” – Aldo Leopold). The essayist must be able to tell readers what the streets of New York look like in winter (“Last night hangs heavy in the morning sky” – Colson Whitehead), or what the upper Mississippi banks look like in summer (“cleared patches in the woods littered with malt-liquor cans and fast-food wrappers, hobo camps with the musty wild smell of an animal’s den” – Matt Power). Neither the narcissist voice, nor the doubter, could remember just exactly what the Utah desert smells like after rain, and how different that is from the bouquet of a Parisian subway station after rain.

Despite the horror and hopelessness (see below) that moves through the world, the essayist must have, even if it is well-buried under the most convincing costume of misanthropy, a deep and abiding love of humanity. Essayists set up beacons, send down ladders. They hold the belay rope, the flashlight, and sometimes even the first-aid kit. The best writers listen for humanity’s heartbeat, and write out the beat of it—sometimes in their own blood, and sometimes to a tune hard to follow, but with a listener in mind.

When Aleksandar Hemon loses his baby daughter to a swift and rare cancer, he says, “One of the most despicable religious fallacies is that suffering is ennobling—that it is a step on the path to some kind of enlightenment or salvation.”

When Ross Gay contemplates the systemic, toxic racism at work in America, he calls for mercy. Without mercy, he asserts, “we will remain phantoms – and, as it turns out, it’s hard for phantoms to care for one another, let alone love one another.”

Lidia Yuknovitch says that if she could go back in time and talk to her younger self,

I’d coach myself. I’d be the woman who taught me how to stand up, how to want things, how to ask for them. I’d be the woman who says, your mind, your imagination, they are everything. Look how beautiful. You deserve to sit at the table. The radiance falls on all of us.

Even one of nonfiction’s well-known curmudgeons, Edward Abbey, meant for the essays in Down the River to serve as “antidotes to despair,” believing as he did, that despair led to “boredom, electronic games, computer hacking, poetry and other bad habits.” Even a stalwart cynic must acknowledge that Abbey’s despair was between him and the desert. He speaks of saving us from our own.

Lia Purpura has “seen how easily we open, our skin not at all the boundary we’re convinced of as we bump into each other, excuse ourselves.” Cheryl Strayed knows that “healing is a small and ordinary and very burnt thing.”

These are real bodies straining across the chasm saying, Here, take my hand.

They essayist is burdened with the need to look, and the privilege to look away. This is the voice of the witness. The voice who says, watch and then, tell.

Sometimes, the looking is uncomfortable; sometimes it is dangerous. Bill Buford spends some time Among the Thugs; John Jeremiah Sullivan goes to a Christian music festival; Susan Orlean watches bullfights—so that we don’t have to. Essayists confront the singular and multitudinous horrors of humanity and life on this spinning rock in space. Essayists document war, abuse, and losses that would be unimaginable but for their words.

But life isn’t just a string of tragedies, enacted at different scales. The nonfiction writer, too, sees the saved child, the triumphs over adversity, the sapling pushing up through cracked concrete.

When Diane Ackerman drives up the Northern California coastline, she stops for a moment near Big Sur just long enough to find a metaphor in a roadside evergreen.

A Monterey pine leans out over the Pacific, making a ledge for the sunset. The pummeling gales have strangled its twigs and branches on the upwind side, and it looks like a shaggy black finger pointing out to sea. People pull up in cars, get out, stand and stare. Nothing need be said.

Mark Twain once stood on the very rim of Kilauea. He wrote about it for the Sacramento Daily Union during a time when travel to Hawaii was impossible for most Americans.

The greater part of the vast floor of the desert under us was as black as ink, and apparently smooth and level; but over a mile square of it was ringed and streaked and striped with a thousand branching streams of liquid and gorgeously brilliant fire! It looked like a colossal railroad map of the State of Massachusetts done in chain lightning on a midnight sky. Imagine it - imagine a coal-black sky shivered into a tangled network of angry fire!

But the witness also walks away. He is Ishmael, escaped to tell the tale. Except in rare cases, such as diaries and letters, the reader does not have to worry whether or not the narrator of a work of nonfiction lives through the essay. After the last page, none of us may be safe, but within an essay, the writer lives, though all the rest might perish.

More and more, there are important conversations happening about how the witness can and should find a way to unpack that privilege and acknowledge it. When Sydney Schanberg says good bye Dith Pran, he does so with the burden of his own impending escape from the Khmer Rouge. “He saved my life and now I cannot protect him.” But his burden is also his freedom.

The essayist must live with the horrors she’s witnessed, and speak them. She must know, deeply, the readers she’s hoping to reach. And she must find a way to envelop those readers in a complete world of her own recollection. That takes more than a blend of narcissism and doubt, it takes hope.

I do not send these words out into a void. I send them to an Other. And I must hold some sense of hope that just as the act of writing will change me, so the act of reading what I have written will invite change.

I’m hoping of course for a lovely letter from an editor, ideally from a paying market. I’m hoping for a congratulatory note from the judges. I’m hoping that the journal wants my essay and that the press wants my book. I’m hoping to hear from a reader that what I wrote moved him. But if I’m being honest with myself, this is the hope of the narcissist. And the converse fears of silence are the fears of the doubter.

At the heart of the act itself, I write to cultivate my own clarity, my own empathy and my own growth—but when I send that writing out into the world, it is not just an act of narcissism. It’s also the ultimate show of optimism.

I don’t mean to suggest that every essayist is an optimist. Far from it. But that there is an inherent optimism in choosing to devote a large part of one’s life to writing. And this isn’t just the optimism of tenure or a New York Times best seller.

Joy Williams, for example, is rarely “sunny” in her collection, Ill Nature. But in the last line, she reaches beyond her condemnations of human folly to assert that “The writer writes to serve—hopelessly he writes in the hope that he might serve—not himself and not others, but that great cold elemental grace that knows us.”

When Annie Dillard is asked by a reader who might teach her to write, Dillard replies,

…the page, which you cover slowly with the crabbed thread of your gut; the page in the purity of its possibilities; the page of your death, against which you pit such flawed excellences as you can muster with all your life’s strength: that page will teach you to write.

That writing itself might be a kind of alchemical process, and that some cold, elemental grace might teach me, might change me from possibility to probability, that is the voice of optimism that a writer, or any artist, needs to make ART from her desires.

Chelsea Biondolillo's prose has appeared in Guernica, Brevity, River Teeth, Shenandoah, Hayden's Ferry Review, DIAGRAM, and others. She has an MFA from the University of Wyoming in creative writing and environmental studies, and is currently the 2014-15 Olive B. O'Connor nonfiction fellow at Colgate University. She can be found online at http://about.me/chelseabiondolillo and http://roamingcowgirl.com/.