Writers on Writing #44: Forrest Roth

Writing within Sound: A Reflection

Silence is not always golden to me. I often can’t write in it, or refuse myself writing in it; and, if being surrounded by it, I wait for a disruption to jostle the enveloping blankness. Better that I try my hand in a crowded café—with or without music playing from some corner—as I may find a snippet of dialect or dialogue to use, send me on an errand. Music is preferable, however. Conversation itself, especially good conversation, has an evident musical quality I believe all thoughtful writers desire to follow, yet listening to any distinct sounds not altogether tethered to the human voice while writing or typing, I have found, allow promising conditions for worthwhile sessions, which now follow my practice like self-insistence.

The writers who require an insulated study to compose prose sonic-proof, not so much as a whisper entering the room—do they ever miss music? Do they hum a tune to themselves without realizing it? It’s difficult for me to imagine that they don’t, much in the same way that it’s difficult to imagine there are people who hate music. Since listening to music was a substantial part of my early upbringing, I try not to judge. There is disruption, and then there is distraction. It can be a fine line. Everything milling about in the head can get crowded quickly. I sympathize that much, at least.

For me, dealing with that fine line depends entirely on the selection of sound. Lyrical music can be the distraction, while instrumental or non-lyrical music can be something more than inspiration. There’s nothing remarkable by suggesting how certain kinds of music we respond well to can prompt our writing beforehand, even directly or indirectly give us viable ideas for it in the process. And, of course, all music can be practical in helping inform a narrative and accentuate its specific parts as it unfolds before us, such as in operatic theater or movies, contingent on its selective properties. But listening to non-lyrical music or the sort while writing I find to be an undervalued technique, if only because a prevailing thought deems that silence must overcome for concentration’s sake.

Some time ago, I might have agreed with that. I think I gave up attempting writing prose in what felt like competition against lyrics playing around me. I still have difficulty picking out words of my own while other words are being sung or (as is the case with my tastes) yelled at me. Instrumental is favorable, regardless of the genre, though it was my introduction to electronic music—especially of the obscure variety—as an undergraduate which gave me the clue after a steady diet of post-punk and indie sought to control my writing too much. Or more than I wanted it to, at least. A necessary intrusion reaching its limit when I wanted more out of myself, my prose, I remember.

Over the last several years—and likely longer than that—I’ve been intrigued by the potential relationship between writing and non-lyrical music, particularly electronic in its myriad forms. More than any other genre of music, I think, it allows a direct and unfiltered engagement of the writer’s mind with the unfamiliar, something which I usually feel my writing needs to start with first. Brian Eno’s ambient albums of the 1970’s provide a fundamental method toward this: music, or pure sound, as cyclical, repetitive background, not linear foreground, thus allowing the mind to relax, find patterns in imagination, follow them, and adjust deliberations as they happen, letting the writer’s own words arrive in tandem with the sound when the mind is ready for them. This is in aid to whatever pre-writing writers would like to accomplish before setting out, to be sure. Other elaborate, layered forms of electronic can provide what Eno has referred to as “fictional psycho-acoustic space,” the idea, as I read the term, that the writer’s mind will skirt the division between background and foreground, enter and populate the sound, as well as find words for it. Find stories in it.

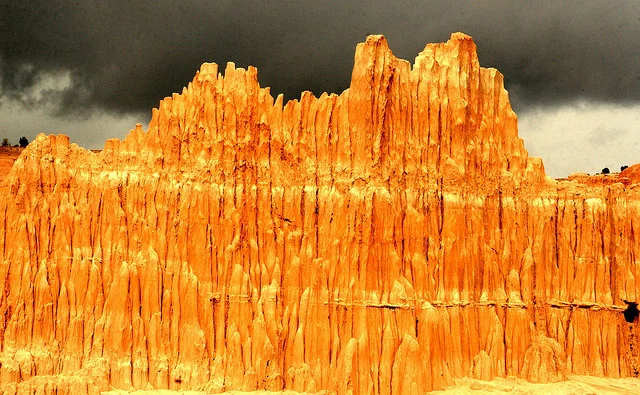

Recently I completed a prose poem novella commenced in sound, its rough material composed under the influence of many hours of electronic along these lines. Many of my album selections for writing sessions came from an Italian “drone” artist, Alio Die, who specializes in mixing electronics, loops, field recordings and samples with various ethnic instrumentation, allowing for a trance writing which many authors have lauded as healthy estrangement from plodding, conscious direction over composition. The particular archaic pastoral theme for this novella I was writing within necessitated this estrangement, and perhaps I grant the music even conceived the project. I don’t think I could have written and finished the manuscript otherwise: I needed to be bothered slightly enough to bring it out of my head.

Eno-style ambient, other sub-genres within electronic music, and all instrumental music in general may inform prose towards such possible narratives which are still in our minds, as we write them; and yet these sounds do more than merely inspire and allow creativity. Later, considering the written work, listening to those sounds again, I begin to understand how music also can affirm the writing it helps after the fact. It reassures me that I haven’t searched in vain for what I wanted to write before I even knew the words I wanted.

Music, then, is one of my best readers.

Forrest Roth recently graduated with an English PhD in creative writing from University of Louisiana at Lafayette. His novella Line and Pause is available from BlazeVOX Books, and a prose poem chapbook, The Sullen Pages, is forthcoming from Little Red Leaves. His work has also appeared in NOON, Denver Quarterly, Caketrain, Sleepingfish, NANO Fiction, and other journals. Links can be found at www.forrestroth.blogspot.com.