Writers on Writing #13: Todd Fredson

Egalitarian Parenting & Writing: Effects on Process and Aesthetic

With two young children I am required to be patient (Yep, I hear you. I will walk the plank and get wet. A pirate ate the flag! What?! Eww, so salty…), exhaustively patient, while doing more with the same amount of time. I frequently recall something Alberto Ríos told me. One of my MFA committee members, when he learned that my partner and I were going to have a child, Ríos exclaimed, “you won’t believe how much you will be able to get done!”

With a three year-old and a five year-old, I do my writing in shorter moments. I hold thoughts longer; I hold a thought and turn it over many times before it appears on the page. Though time at a keyboard is less, my poems are becoming longer, it seems. Associations within the poems and connections across a manuscript are more explicit now when the poems hit the page.

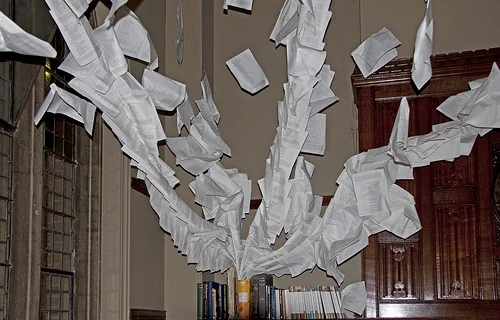

And when I write I am less fastidious. There is less hesitation, self-rebuttal, pity, pensiveness, etc. I can’t clean up as I go, and this is helpful for me, to honor revision as a more separate process. Practically speaking, I have likewise learned to live and work in a space that is not always tidy. The idea of an organized workspace seems romantic now—kitchen in order, the trash taken out before sitting down to write. Now those squished oranges might stay on the floor while I deposit a thought at my computer. Things are often messier—wilder, I might say euphemistically.

I am always interested in hearing from other parents, dads particularly, who are engaged in writing and egalitarian parenting. Fiction writer Tony D’Souza, who also has two young kids, told me that parenting has strengthened his writing discipline. If he doesn’t take advantage of his time to write there is no way to make it up. His kids also provide him with a sense of contact with future readers. “I'm even prouder of the work I've done knowing that my kids will likely read it one day. I do wonder as I write now what my kids as adults will think of my work; it increases the pressure not to embarrass myself, and adds another layer of self-editing. I think, ‘Will Gwen like this when she's twenty? Will she be bored by it? Will she think it's silly or not worthwhile?’"

When I mention that, for me, there is less hesitation or pity or rumination-unto-complacency, I am simply saying that I take writing seriously in a way I didn’t before. As Tony puts its, “writing and staying up late do affect my patience with [the kids] because they are so young; I definitely make sure as I write that the project feels worth the price that's being paid in regards to happiness and quality of life.” Parenting, perhaps, can provide a counterweight by which to measure the writing imperative.

This urge to make the writing “worth it” probably has heightened my commitment to craft; I think I have begun to respond to this sense of futurity in regard to subject matter also. Every generation probably feels itself responding to the next generation’s hopes and fears (or our projections of them; particularly as a Western culture, trusting the privilege of our material well-being and stability, we seem to invest much of our imagination in the future). My own poems, I think, have begun to pay special attention to grieving, grieving as a process that keeps relationships clear. This includes relationships beyond the anthropocentric. How can the heart respond to the loss of glaciers, to life in a period of mass extinction? These questions suddenly seem as basically present as questions about how to get those tricky foil wrappers off of chocolate coins.

This attention to grieving, to loss, must come as well from regaining access to my own youth. Naturally, I find myself reexamining my relationships with my parents, seeing them as actual people in my memory, and then seeing myself through their eyes. This is not particular to being a writer—for any parent, perspectives shift—but as a writer, I regard these sensibilities—like the distressing of time, like emotional stamina—in terms of their influence on my process and aesthetic.

Beckian Fritz Goldberg suggested in an interview that, “[m]emory is a poet’s biggest bag of tricks, especially childhood memories, which are saved before you’re able to form conclusions about an experience.” As a writer who spends hours everyday with his kids, I would suggest that parenting might offer new ways of feeling around inside that bag. I certainly love the opportunity for time spent in the vicinity of that inconclusiveness.

Todd Fredson’s poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, Blackbird, Gulf Coast, Interim, Poetry International, West Branch and other journals, as well as anthologies. He received his Master of Fine Arts in poetry from Arizona State University. He is pursuing his doctorate in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Southern California. Fredson lives with his partner, poet Sarah Vap, in Santa Monica.