Each Breeze Began Life Somewhere As a Little Cough by Christopher Citro

Editorial intern Brandon Hansen on today's bonus essay: Christopher Citro’s essay will sweep you up and spin you around, layering you in fallen trees and home explosions and radon, just for a start. His sharp wit and careful obsession with wind effectively captures the intimate and the violent, the lovely and the tragic.

Each Breeze Began Life Somewhere As a Little Cough

They stood up and stared about them rather stupidly. It seemed not credible that all this had been done by a current of air. Mr. Thornton patted the atmosphere with his hand. When still, it was so soft, so rare.... --Richard Hughes, A High Wind in Jamaica

The first time a tornado almost killed me was in Lawrence, Kansas. Hiding in the basement of my college rental, listening to the NPR announcer provide updates of one funnel cloud on the ground just to the south of us—moving north—and another on the ground just to the west of us—moving east. Sitting there in the dust with my girlfriend and one of two of the other confused tenants, I thought, so this is how it happens. This is how someone dies because of basically wind. At one point the announcer, whose studio was nearby and also in the crosshairs of both tornadoes, actually laughed as he described how they were bearing down directly upon us. Black humor was invented in the 1960s but now it belongs to anyone.

I remember looking around me in that basement for maybe an old bathtub or something that I could turn over Sarah and me so we'd live. Sweating there in the shadows, I remember noticing some of the junk left by years of students, a brass headboard, boxes spilling clothes all dust gray. The acrid scent of damp cardboard and stale soil. I don't remember how it ended. At some point we stood up and walked out of the basement.

About a year after I moved out, that house blew up. Gasoline from leaking tanks beneath a station across the street seeped into the basement and an errant spark set the fumes alight. Dangerous air got it eventually. The local news interviewed one tenant who was out at the bars when it happened. When he came home there was no home left. Only news crews. "It's a surreal experience," said Glenn Baughman, who arrived about 4 a.m. to his upstairs apartment engulfed in flames. "You can't really go crazy. You can't really go anything."

*

On my basement library bookshelves, 11:44 pm, September 15, 2016:

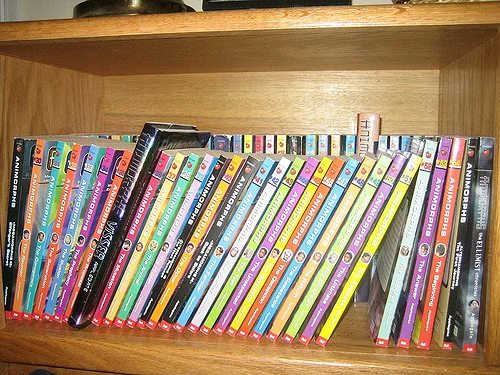

The Complete Soulwind, Scott Morse. Never read. Inherit the Wind, Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee. Read long ago. So the Wind Won't Blow It All Away, Richard Brautigan. Read and re-read. Windblown World: The Journals of Jack Kerouac 1947-1954, edited by Douglas Brinkley. Read. Wind in a Box, Terrance Hayes. Read and re-read. Wind Song, Carl Sandburg. Never read. High Wind in Jamaica, Richard Hughes. Read last month and immediately reread.

*

"Guests who spend the night get to sleep on the air mattress. We blow it up tipsy before bed and get light headed." If I wrote that a year ago it would have been true. Last month we ordered a loveseat that folds out into a guest bed. The UPS guy carried the massive cardboard box on his back up our hill—bypassing the perfectly serviceable driveway—while I watched from the stoop hoping that he would not fall and die.

Assembling it later that day, my girlfriend and I found that the springs came compressed, enclosed in an airtight plastic wrapping. "Stand back," I said, being helpful, as I pierced the clear membrane and the coils expanded and the guest bed took its first deep breath. Each time a visiting friend or family member sleeps on it, it will take another. Last Saturday we made love on it then napped. It took a few deep breaths in a row. Then it took a break for a while. When we woke we noticed the cat had curled up at our feet. That was another, a little black cat shaped breath while we were asleep, holding on to one another and breathing without thinking of breathing.

*

During the four years we lived in our last place, two cottonwoods blew down. The first collapsed sometime during the night, and I noticed it as I looked out of the kitchen sink window, tipping back a morning glass of water.

Eyes: A huge tree is lying sideways in the backyard. Brain: Huh? Eyes: A huge tree is lying sideways in the backyard. It looks like a tree. On its side. Brain: Those branches are supposed to be way up in the air, not in the grass. Did I do something wrong? God, I hope not. Is that really a tree on its side? Eyes: Yep. See?

And so on.

The landlord hired two guys to come chop it up and take it away. I set up my camera in the master bathroom and made a time-lapse movie of the guys working. Filming them from the second story window, they looked like mice, highly industrial mice with chainsaws and wheelbarrows. When they were done, they even sucked the sawdust up from the grass with a Shop-Vac. Have you ever seen a mouse vacuum a lawn? It changes you inside.

Several years later another windstorm brought down another massive cottonwood on the other side of the yard. I was standing in front of the second floor sliding doors, turned away, talking to my girlfriend when it started. At the first sound of crashing I snapped around to the glass.

Eyes: A huge tree is falling in the backyard. Brain: What—again? Eyes: Look. It's still falling. Ears: Hear that crunching sound? Feet: Feel the house shaking under you? Brain: What the hell's going on? Eyes and ears and feet: (Sighing) Brain: I get it. A tree's falling over. But that's not supposed to happen. Holy smoke! A huge cottonwood just got blown down right in front of me! Is my girlfriend ok? Is my cat ok? Am I ok?

I looked back over my shoulder. Sarah was ok. From where she was sitting she couldn't see the tree, but she could hear it and she could feel the house shake. She was looking at me with her mouth open. Our cat was standing at my feet, looking up disapprovingly, wondering when I was going to give her a cocktail shrimp.

*

Alize, Bayamo, Caju, Chinook, Cordonazo, Diablo, Foehn, Haboob, Harmattan, Libeccio, Mistral, Nor'easter, Ostro, Pampero, Passat, Santa Ana, Simoom, Sirocco, Squamish, Tramontana, Williwaw, Wreckhouse.

*

Visiting the Syracuse online newspaper to see if there are any Local Winds associated with the area, I've found an article about a 113-foot blade which dropped off a 200-foot tall, 187-ton windmill this last February about 45 minutes southeast from the city.

The blade appears to have fallen off at about 9:30 a.m. today, and town officials think it may have been caused by a bolt failure, said Paula Douglas, Fenner town clerk. Town officials didn't think the wind had anything to do with the incident.

The article contains a photograph of a two-arm wind turbine that should be a three-arm wind turbine. Its missing limb lying at its feet in a snowy February field, pale blue highlighted by furrows of turned earth. The two remaining blades hanging down and out like a frown, like arms reaching for what's lost, in a Renaissance composition trying to cradle the fallen limb. A deep-frozen Madonna and Child or renewably electric Pietà. It's the middle of September, but I can't get that image out of my head. A good reason to take a field trip.

*

Fenner Wind Farm, Madison County, New York

Me: Could you imagine one of those arms falling off right now? It'd make my brain melt.

Sarah: It's kind of scary just being close to one. Plus when the clouds move it makes the sky move. And it makes you feel like you're tilting with the—

Me: You just used the word "tilt" by a windmill.

Sarah: (Singing lustily) I am I, Don Quixote, the Lord of La Mancha. My destiny calls and I go. And the wild winds of fortune will carry me onward. Oh, whither so ever they blow.

Me: (Mimicking the sound of a voice over a telephone) Uh… Hello? This is Destiny calling. Now go!

*

Blue-green algae produced our planet's oxygen atmosphere many, many years ago. Longer than before Stevie Wonder even. Stevie Wonder was originally called Little Stevie Wonder. He was that young when he was discovered. He played the harmonica with wondrous skill and that's why they signed him to Motown. When he blew in certain ways into a tiny organ with precise and tinier tunnels it made music, which is organized sound waves that travel on the air, enter our ears, and make us go "yeah" and "groove" and "right on" and form other vocables of pleasure in the head. If there were no air the waves would have nothing to ride. You can try the experiment. Put your hifi into a vacuum chamber. Step inside. Get someone smart to suck all the air out. Then crank up some "Uptight (Everything's Alright)," young Stevie's 1965 hit single. Your speakers will flap but you'll hear nothing. You'll have to put up with this for 10-15 seconds, which is approximately how long we can live without breathing in a vacuum.

*

Some winds do have delicious names. Speak them aloud, and your breath forms heavy, curling shapes in your mouth. Simoom is one. A sirocco is a wind that pours north out of the Sahara into the Mediterranean, a Bogart film, and a Volkswagen—

As fast and powerful as the desert wind it's named after.

A foehn wind is a swift, unexpectedly warm current that forms down the lee slope of a mountain barrier. I don't actually know what that last bit means, but I think I experienced one of these in my twenties. A girlfriend and I had traveled to a mountain in Virginia to take part in a sweat lodge ceremony. One evening as we were glowing inwardly like little flesh ovens from the effects of several hours perspiring in a dark cramped space followed by a dip in a frigid, spring-fed stream, walking through the autumn air, a sudden hot wind came humming down the slope, abruptly raising the temperature from the upper 50s to the balmy 70s. People came crawling out of their tents in the field, some nude, most with their mouths hanging open. Some started running. Some leaped around whimsically in case something mystical was happening. After a few charmed minutes the wind ceased. The temperature dropped again and we stood around under a sky full of spinning stars. We looked up at those little lights and at the distances behind the lights. The foehn wind gone. The air quiet again, invisible as always.

*

Me: The radon fan on the side of our house makes more noise than this thing. So what do people complain about having wind turbines in their area? Because, ok windmills. Anybody other than Satan's gonna think it's a great deal. And then you see things where people are complaining and it's sound apparently, and also something about them messing up birds. But we're surrounded by them now and there's just nothing loud about it.

Sarah: And the place is not littered with dead birds.

Me: There's cows all over on the ground but they were never airborne to begin with. There is a sound, but it isn’t a shrill, high-pitched grind or anything unpleasant. It's kind of like a quiet wuff.

Sarah: It's got a little hum to it. And occasionally you can hear the wind buffet. A whoosh.

Me: A whoosh over a hum. I'm with you there.

Sarah: It almost sounds like waves.

*

High above the sweat lodge, someone had hung wind chimes. They must have been over 60 feet up into the branches of a nearly leafless beech. Walking up from the forest path, I heard the sound of distant tinkling and thought, how did someone get those up there? With a crane, with an arrow and some string, maybe an unusually biddable hawk? Breezes that high are different than those at human level. The chimes made present to us on the ground what was otherwise not present. Their jangle pleasantly muffled by the distance. Which was nice.

*

Today the radon abatement guy came over to remove the testing apparatus which will tell us if the two grand we spent actually results in us having less radon in the basement. Our numbers were below the EPA action levels to begin with, but we just bought the house, we want to live it in for a long time. Lung cancer would get in the way of all this living, so it seemed worth the expense to see if we could get the numbers even lower.

As radon decays, it produces other radioactive elements called radon progeny (also known as radon daughters). Unlike the gaseous radon itself, radon daughters are solids and stick to surfaces, such as dust particles in the air. If such contaminated dust is inhaled, these particles can stick to the airways of the lung and increase the risk of developing lung cancer.

When the guy pressed the button to see the initial readout this morning the number came up 0.4. The level of radon present in the ambient air outside—what you get sitting in the grass or pulling a lawn chair into the shade or following your lover across the lawn to try to get hold of her—is apparently 0.6. So now there's less radon in our house than there is in our backyard.

Me: (Upon hearing the news, something like) Yeah (or) Groove (or) Right on.

*

To survive a sweat lodge it helps if you get your head low to the ground. As each successive load of bonfire-heated rocks are brought in, as the leader of the ceremony sprinkles water which immediately transforms into choking steam, as dried herbs are dropped and flame into temporary stars, filling that weird, dark world with interesting scents and smoke, breathing can get a bit dicey. It helps to hold some spit on the front of your tongue, then make a kissing shape with your lips, as if you're going to whistle but backwards, drawing the air through your saliva which cools it. You make a sort of hookah of your body so your lungs don’t singe meanwhile the rest of your body is hoping that you don't die.

In the darkness and the hot air people pray, silently and aloud, for themselves, for family and friends, for physical and psychological healing, for whatever burdens they've brought with them into that sweaty little tent.

*

How radon mitigation works. Some guys come over in a white van and drill a hole or three in your foundation. They lower a plastic pipe into it and vent it outside. Outside the house, inside a plastic box, there's a fan. The fan sucks air out from just under your basement where the invisible radioactive gas collects as it rises from shale, granite, schist in the soil. You can't do anything about that. So relax. It's just the way things are. They've even found radon on the moon.

The fan is no stronger than a vacuum cleaner, yet this is enough suction to pull the radon gas out from under the house and throw it into the sky to disperse and be somebody else's problem. In fact before they install the permanent fan, they dig a few small holes to test how well the draw is beneath the whole foundation. They stick an ordinary Shop-Vac in the vent to provide the suction. The guy who gave us the estimate told us he wished he'd have invented the technology to do this. "It's so simple and the man who thought of it in the 1980s is a millionaire twelve times over by now."

"This one couple I met, they raised a whole family then checked the levels after the kids left for college. Through the roof. For fifteen hundred they could have had the gas sucked safely out before it had a chance to sit in the basement with the video games and the bunk beds. It's too late for regrets. That's for damn sure."

I asked him if it was safe to hang out in the yard under where the radon chimney runs up the side of the house. "I'll leave a few hazmat suits when we're done in case you want to have a picnic out there." I realized he was joking after about half a second. For half a second though I pictured Sarah and me sitting in the lawn in human Ziploc bags sipping chilled white wine, trying to enjoy ourselves under a radon cloud in our new yard.

The fan runs constantly and should last 10-15 years. There's a slight breeze underneath our house right now. It's pulling away danger. We can breath as much as we want and it's okay.

*

Thing is, I don't actually like wind chimes. It's enough to feel it—I don't need to hear the breeze as well, or at least the breeze doesn't need me to give it a mouth piece. That's what pine trees are for. Packing up this summer I couldn't find the mouth pieces for my trumpet. Neither of them. And though I haven't played in decades, I'm perplexed by what I thought I was doing I needed two trumpet mouthpieces but not the trumpet. Drunk people know the feeling, waking up the next afternoon wondering who they need to call and apologize to. That's what turning 30 felt like. And since we bought this house we've changed some things without thinking twice, switched off that awful buzzing light outside for one. But I hadn't the ventricles to throw out the chimes—the carved cardinal's crimson almost weathered away. I moved them to the side of the shed, part of my brain saying to the rest of my brain, Why am I bothering to rehang these? It's only a few bamboo tubes anyhow. The wind comes, it sounds like a very small marimba a very long way away. We're little, in a circle in a clearing. Huge dark leaves surround us. There's a light. We're holding it in our upturned hands. Living long enough to gather the fragments.

*

Me: There's a child yelling in the distance. Joyfully. There's a lot of little butterflies floating around here. What color are they?

Sarah: Lots of colors. Some yellows and some white ones.

Me: What are they doing?

Sarah: Fartin' around in the flowers.

*

When you blow into a fire you make it get bigger. Blowing too hard can put the fire out. You blow a candle out by separating the flame from the wick with the power coming from your two little cheeks. You're like one of those gods or cherubs in one of those Renaissance paintings. You feel like a big shot. Trick candles have a little gunpowder woven into the wick which reignites merely from the warmth of where the fire was. Then you have to blow it out all over again. Trick candles are a novelty. People buy them to make some people confused and other people laugh. Whoopie cushions are pink rubber bladders with open valves that when left alone crimp and hold breath in. When sat upon, the crimp loosens and the breath escapes with a flatulent blat. The wind someone's breath just before. The breath of the practical joker. Usually an uncle or someone just like an uncle. A brother in law. I can't remember the last time I saw trick candles in action. I was a child I suppose. The last time I heard a whoopie cushion in action I was also a child. The last time I repainted a deck to protect it from the ravages of a long winter was last week.

*

When I was little I'd run into the backyard during storms to watch the trees sway, and my mom would call me—by my full name—to come down to the basement. Now that I'm big, my girlfriend calls me—by my full name—to come down to the basement during bad storms. Once in a rental without a basement, we ended up in our study closet—the one with the handle that couldn't click shut properly—with each other, a radio, a windup flashlight, and our confused cat. The cheap wood paneling inside offering little reassurance in the event of a tornado.

As we stood pressed together, sweating in that darkness, listening to the buffeting and the radio, I held the door tightly closed with my arm. If things got really bad, it would be the storm vs. my right arm.

*

I have a failed poem from last year. At the back corner of the circle where our rental sat, the wind regularly rushed and smacked flat against our living room. In the winter, before we sealed the windows with plastic sheets, we'd see snowflakes hover above the couch. In the summer, neighbors' trash ended up plastered against our fence. Once I found a notice of service termination for the rental next door. They owed National Grid almost five thousand dollars. How you do get to owe the electric company almost five thousand dollars? When they moved out they chose the middle of the night to do so. The sound of a U-Haul back door rolling up at two a.m. is a very specific sound.

I can't seem to let go, to send this poem packing. When I read it, I'm back in that old house, the place from which it felt for a while like we'd never escape. The poem begins:

The wind's rising now and if the wind gusts hard enough to knock a tree down on me, I want to say I wouldn't mind.

And ends:

In the evening after supper, we clasp hands with our mates and stroll the circle under the swaying branches. We see fists and biceps in the sky and take comfort from that.

The title of the poem: "Each Breeze Began Life Somewhere As a Little Cough."

*

I hope the neighbors don't complain. I keep taking my clothes off on the front deck at midnight or call it one a.m. I don't leap about. I sit quietly to feel the breezes on my all-parts, the stars on my skin. The winds that rise up the slope animate the evergreens and I just can't help myself. The new robot vacuums three times a week. You leave for work with all stray cords tucked into the shelves because it can't handle wires. I killed a tick—or something like a tick—this morning on the underside of the glass patio table. I used one of the rocks we brought back from Lake Ontario years ago and keep around to make us think of the lake when otherwise we'd just be worrying about stuff. And I tried not to worry about everything that crawls over me in the night, everything I can't help letting enter. At a certain point I give up and bring myself to bed where you're already sleeping naked beneath the covers. I say bring myself as if I'm outside myself, leading my fumbling body by the hand to what's good for me. Which is precisely what's happening.

Christopher Citro is the author of The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy (Steel Toe Books). He won the 2015 Poetry Competition at Columbia Journal, and his recent and upcoming publications include poetry in Ploughshares, Crazyhorse, The Missouri Review, Prairie Schooner, Best New Poets, The Iowa Review Blog, and Poetry Northwest, and creative nonfiction in Boulevard and Colorado Review. Christopher received his MFA from Indiana University and lives in Syracuse, New York.