Part Muscle, Part Metaphor, Part Pain: A Review of Andrea Scarpino's What the Willow Said As It Fell

Andrea Scarpino’s What the Willow Said As It Fell begins with an epigraph by Florence Williams: “Our bodies, I learned, are not like temples. They are more like trees.” The narrator’s desire to heal, or at least understand, her damaged body is one of the driving forces between this book-length poem. The narrator suffers from chronic pain that evades diagnosis and eludes even description with standard language. “Pain,” she says, “is like nothing but pain.” And if this is true, how can it be described for a reader?

But one of Andrea Scarpino’s strengths is that she is willing to examine chronic pain using every tool at her disposal, including historical accounts of ash trees, definitions from reference books, and found poetry from her own medical records. Scarpino is masterful at anchoring us in concrete images, whether of beautiful spring mornings and ash-blackened bodies, or clumps of nerves and dim doctor’s offices. She also immerses the reader in the same medical jargon whose complexity and abstraction overwhelm her narrator, reminding us that pain can never be fully concrete when there are terms like “uterine fibroids” and “endocrine disruption” associated with it. In many poems in this collection, Scarpino reduces the body to a list of symptoms and proposed responses, and these sections are effective in reminding readers of the effect illness can have on one’s enjoyment of life; the pain and a solution to it become more important than all those other beautiful memories we have.

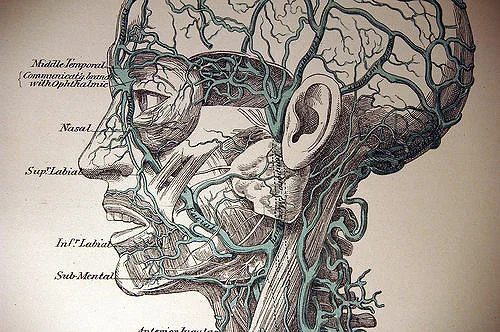

On a lyrical level, the book is poignant. Scarpino finds beauty in the fragility of life, giving attention to such images as “A baby born/with damaged lungs,” with its “Body its own mooring.” The narrator cannot help but regard the “radiated branches” of her veins as “beautiful” and “arborescent.” Throughout the text, the narrator recalls spring mornings spent in sunlit fields, times when the pain was momentarily latent. As she fights for a reprieve from the pain, Scarpino manages to remind readers of the beautiful life experiences she could be having while also reminding them that the pain is omnipresent; the word makes an appearance on almost every page, refusing an easy metaphor or even a synonym.

Scarpino does not settle for a simplistic description of chronic pain, and instead she adeptly describes the deleterious effects of pain on the mind. In many scenes of the book, the narrator is “so often alone,” left with nothing to do but think of memories before all this happened and hope for an end to it. Throughout the text Scarpino repeats a comment rendered by the narrator’s mother, “What is remembered in the body/is well remembered,” refusing to placate those who hope for an ending in which the pain is simply overcome. Pain is like nothing but pain, but because of Scarpino’s willingness to experiment with form and style, readers come away from the book with a greater understanding of the nature of suffering. This work speaks to all of us in our imperfect bodies, whether we suffer from chronic pain or not, because at the end of the day our bodies are trees—and as Scarpino writes, “The borers always came/always to suffer, always to break—.”

Benjamin Kinney recently graduated from Northern Michigan University, where he holds an MA in English. He has previously published reviews at Heavy Feather Review and the Ploughshares blog. He lives and writes in Marquette MI and runs an infrequently updated blog at benjaminkinney.com.