Writers on Writing #108: Wendy A. Gaudin

Unwanted Letters

Ever since I was a little girl, with two heavy braids hanging down my back like the long, lit traces of sprinting stars, my gaze has been strewn with words. Imaginary words in every part of our house: words on the carpeted stairs where my father angrily threw a basketful of unfolded laundry, words at the circular kitchen table where my mother wound my hair onto huge, plastic rollers and stuck them with pins, words on the floor of my sister’s bedroom, littered with fringed leather purses and lipglosses and New Wave albums, words in the sunken living room with its picture window, contemplating the adjacent olive tree. Words conjured my surroundings, the names of things that were never there or things that were so mundane that I can barely recall them now: like the scene in The Color Purple, where little Nettie is teaching little Celie to read: attaching the names of things to things and spelling them out, I scramble for memories by seeing the words there. Fireplace. Typewriter. Swimming pool.

I am standing brown-skinned and pigeon-toed by the edge of our pool. I am wearing a mustard yellow two-piece bathing suit and I am looking down at my feet. It must have been my birthday because my friends are lined up next to me, all of us standing on the edge of the shallow end of the pool, where I spent countless hours in the summertime. We were nine. There you can see Danielle, whom my mother said was fast, and Allyson, who is wearing a pale pink dress, and Faith, who became a rabbi, and Jana Talley, who once told me that I was adopted because I didn’t look like my mother.

We were skyscrapers in our little dimple between the mountains, we little girls from The Valley.

I am sitting brown-skinned and left-handed, at the kitchen table that overlooked the swimming pool if you leaned forward and craned your neck to the right, my father is next to me, his long-bony-fingers-like-mine drumming away on the keyboard of his electric IBM, his mimeographed notes on the gestational iterations of the Hyla regilla treefrog broadcasting their strange chemical smell throughout the kitchen, his herpetology books punctuated with random sheets of yellow notepaper, and my fingers are drumming away, too, on the keyboard of my own typewriter: a baby blue Sears Holiday. I am writing letters to my dead cousin, August, who took a mortal tumble down an elevator shaft at a conservatory in Germany. Dear August, I write, we have a new dog. His name is Chico.Dear August, I write, I am a very good swimmer. In an old photograph, August is wearing bell bottoms and a blue sweater and a woolly moustache. We are sitting on a half-wall parallel to the swimming pool, me in my long braids, my sister holding one of our pet ducks, and August is smiling.

In my family, I am the letter writer. The Epistolarian. Our history is decorated with all of the letters that I have written. Letters to my mother that broke her heart. Letters to my father that he never answered. Letters to my father that I mailed to my mother because I couldn’t bring myself to send them to my father. Letters that mark the watershed moments of our collective past: the marriage ended, the house sold, the fire, the earthquake, the wedding, the coming out, the treatment, the marshmallow-white baby grand piano. My letters are not celebrations. They are not fixed with bright-colored balloons or silly-sweet stickers. No one looks forward to my letters because they usually record something that we are unwilling to talk about. Letters to my sister that sound like public policy from an age that no one wants to return to. Letters to my great-grandfather who died in 1964. Letters to my whole family that caused everyone to hold their breath.

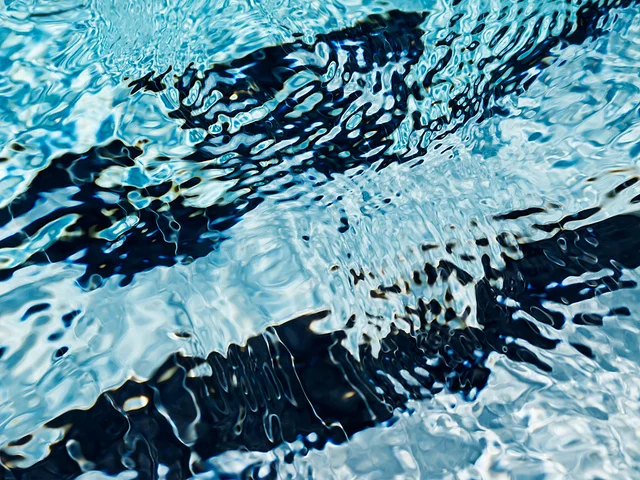

Sometime around 1977, workers arrived and dug a giant hole in our backyard and filled it with the concrete impression of a rectangle. My mother enrolled me in swimming class. I earned my first diploma, which distinctively hung on the wall of my upstairs bedroom. Since then, I’ve been swimming. I walk into a natatorium and the chlorine smell triggers my nostalgia like the smell of corn bread would for a Great Migrant in some snowy city up North. It brings me back to the endless summers in the pool, my grandmother floating on the Styrofoam lounge, my sisters and their friends who were sweet to me, the birthday parties with my friends whose families put them in private school when Los Angeles began busing black kids to The Valley. I get into the water and swim like a writer: decisive, fluid, long strokes. Keen to those around me, careful not to splash. Repeating the same movements over and over, with my eyes open or closed, depending on whether or not I’m wearing goggles. My hands out ahead of me, guiding me, pulling the rest of my body along, my hands defining the path and the direction that I will take. I hold my breath and a garden grows. The light above me is flashing and crenellated. My body: suspended and completely surrounded by words. Wet. Transparent. Alive.

Wendy A. Gaudin is an American historian, an essayist, a poet, and a university educator. She is a descendant of Louisiana Creoles who migrated to California.