Our Bodies, Our Archives by Barrie Jean Borich

She wears her hair in a tall blond beehive. The first time I saw the documentary, I couldn’t stop staring, the freckles barely visible under her face powder, the unflinching gaze. She looked like my childhood southside Chicago babysitter, missing only a Virginia Slims cigarette and a can of Tab. She’s the one who now, when I re-watch the 1977 documentary The Word is Out on DVD, is so matter of fact, so hey this is who I am, OK? I fell in love with the woman next door so they took my kids, but still I can’t change. I fast forward to find the next time she talks, in her starched flowered blouse, a thin gold chain around her neck, sitting on her couch, a knitted afghan at her back, next to her sturdy lover who is a bit shy compared to her, but that’s no surprise. Even if the butch is a top, the femme is usually the tougher of the two. Don’t mistake a lesbian femme for a girl—that’s my survival story.

It’s no surprise that this old school femme and old school butch are way out of lesbian style now, but so is the butch-femme renaissance of my late-1980’s lesbian generation. The hard gender split between two women in love, this magnetism of queer opposite attraction—but too simple now for me to just say I am a femme who goes for the butches. Even my longtime butch-is-the-least-of-it spouse says if we were young today then she might self-define as trans.

Every generation is right to carry on the queer reinvention story, but of course I miss when we were the ones remaking. The resurgence of gender differences between women that made my 20s are for my students the stuff of their parent’s, or even their grandparent’s, generations. I speak to them from an indeterminate space between their parent’s and their grandparent’s lives—the space within which the lesbians in the movies are still wearing stiff tweed suits and tilted fedoras, loners who smoke and keep the books. The space within which Liberace still glitters from his prime time TV specials, my grandmother tittering when he squeezes the puffy fur collar adornments of his white mink coat as he asks, in his high gay closet inflection, “So do you like my fuzzy balls?” The space within which later all that changes, where lesbians sit in first Donohue’s, then Oprah’s chair to say I am, I do, I knew. The space within which Audre Lorde makes up the word biomythography, telling us there is even a special name for our stories, that we are a joyful creative people who get to make up more words as we go.

I teach an undergrad course called LGBTQ Memoirs in the college catalog, but which the students and I together decide to just call Queer Memoirs. This a general education, literature-of-identity class and my job is to teach them that art has layers and indirection and nuance, and that identity is more mutable and strange than what they read in web memes listing “Ten Things You Should Never Say to Your Genderqueer Friend.” We read books related to the kind of books I write, but right away I see that my body—the body of their tattooed Queer Nation era professor, always wearing high boots and dresses with pockets, always waving her arms around trying to get them to listen to her stories about how the generations before them lived— is also a book, a badly organized archive of queer history, of which they know little. This is one of the problems with memoir, not knowing where our bodies end and our books begin. What part of my body is a survival story and what part is just what’s left of what didn’t endure?

The beehive blond and her mannish husband were even more out of style when I first saw the movie, in the waning days of lesbian androgyny, all that utilitarian short hair, plaid shirts, and work boots, as if at all times we needed to be prepared to change spark plugs or cut down trees. When I saw them first, when I was just coming out, I didn’t see all the ways they were a part of my story, but now I know how little I knew then, having not yet learned that what holds us all up is the same force that keeps that blonde beehive from tilting—hard and attentive will, intelligent construction, some support, and some massage, and a whole lot of hairspray. In Queer Memoirs I screen not only The Word Is Out but also other documentaries where body after body parses out identity, each word—butch, stone butch, soft butch, bulldyke, stud, lipstick, fluff, femme, high femme, stone femme—is a marker of surviving in worlds where as Audre Lorde said “we were never meant to survive.”

And we might say the words themselves are our stories—the kind with voyages and conflicts to overcome, drama and tears and finally arrival. We talk in class about the interrogative power of language, about how testimony and memoir overlap but are not the same, about how the ways stories are told changes the meaning of story itself, and I ask them to talk about why queer stories matter. The slender trans student who always sits to my right, the only one in the class who requested we refer to them using the pronoun they, laughs in recognition when I say “The one in the movie with the big blond beehive is my hero.”

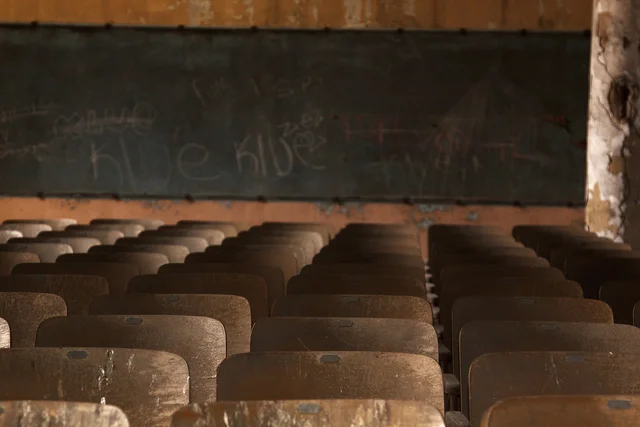

ON THE BOARD

The Elements of Literary Memoir;

- Not just memory but interpretation of memory;

- Frankness and honesty;

- Emphasis on the inner life;

- Attention to childhood and youth;

- Everyday experience as earthshaking as a grand battle.

Like that night in the early 1990s, when the park near the art museum in the center of the city is filling with women. Tattoos glisten under the streetlights and some of the women take off their shirts. The Lesbian Avengers have learned a few good circus tricks and now they’re standing on the tops of cars and are literally eating fire. We pour into the streets, ready to march, no marshals, or street barricades, or police, as there will be tomorrow at the regular Pride Parade. This is the first year of the Dyke March in this city and we march where we please. We start to move, motorcycles first. On the curb are some boys, friends of ours, with signs that read Cocksuckers for Muff Divers. We wave as we pass, me on the back of Linnea’s motorcycle, Linnea muttering about running her engine too slow. We walk, or we ride, and the boys are not the only ones with signs, but there is just one other I remember. A lone woman with gray hair holds a handmade placard that reads LESBIAN FEMINIST. She is not shouting, or smiling, or eating fire. She is just holding that sign. Maintaining her position. At the time I rolled my eyes, but now I get it. Those words were her story.

ON THE BOARD

The Elements of Queer Memoir (the teacher’s list):

- The personal is political;

- Identity is a navigational map between places and communities;

- Heteronormative and cis-normative expectations are enforced in mundane and often invisible ways;

- Queer storytelling makes queer what has previously been considered normal;

- Sex is on the page.

I found more stories from The Word is Out in an archive in San Francisco. The filmmakers were making something that hadn’t been made before, and like a lot of us didn’t know what they were making until they made it. And so they interviewed everyone they could find, cases of tapes, queer story after queer story. I was working in the archives on another project entirely, but the documentary outtakes waylaid me. I kept asking the librarian for more, spent days hunched over a video monitor, observing unedited testimony. The inarticulate hippie. The revolutionary poet in no mood for the children’s questions. The novelist with the dirty laugh. I understood why the filmmakers cut what they cut. The first queer documentary ever had to represent. The subjects needed to be coherent, likable, and friendly enough to keep from scaring the straight people. They needed apparently brave stories. Less flawed than typical human stories. This was not the time for novelistic complication or even a place for a complex documentary rendering of contradiction. The first documentary subjects to speak of the love that dare not speak its name had to speak in a manner that would be heard by an audience barely willing to listen.

But that’s the trouble with conventional story, with linearity, with the desire-plus-obstacle-plus–action-plus resolution equation. Sometimes story inscribes when we need meaning to skew, codifies when instead we need meaning to break free. I want another movie made of all those outtakes. If at first we need a neat arc in order to live, later we will likely need something else, to survive the disappointment when we get to the end of the journey to find the terrain has changed.

ON THE BOARD

The Elements of Queer Memoir (the student’s list):

- The narrator grapples with internalized oppression;

- Unconventional genders and sexualities flourish within queer communities;

- Intersectionality means all queer stories are not the same;

- Memoir is an act of self-redefinition.

I think of the lesbian feminist placard at the Dyke March whenever my story and another, newer, story don’t mesh. Do I carry a placard for a fading story, and if so what does my sign say? My lesbo-queer faculty colleagues and I, at the university where I teach, chatted about this recently. What does the L in the LGBTQ mean now, not as a descriptor but as a political category, in the wake of the beautiful explosion of trans visibility? If gender distinctions as we’ve known them are false, then what is a woman-loving-woman? We were talking about our activist students, how some of them won’t claim the identity lesbian because to their ears the word invokes something like what the lesbian-feminist placard meant to me— a self-rendering stuck in the past, an unwillingness to keep evolving—but much worse. To them “lesbian” equals transphobic, so they identify as trans, or genderqueer, or queerfem, or just queer. They’ve changed not only the names but the lens through which they see what the names are supposed to describe.

Some lesbians my age are enraged by this conversation, charge the youth with erasing their forbearers’ stories, but I think questions keep us alive. Still, this leads me to a linguistic hitch in my own story: a lesbian femme, in love with a butch who might be trans due to not feeling right inside the word woman, leaving me to be a woman no longer defined by loving a “woman,” which within the current alphabet of non-normative identity is what? A trans chosen-family nephew of ours says that makes me a B for Bi, but how can that be correct when the last time I fucked a “man” was in a rustic cabin in 1982—this also being the last time I ever slept in a rustic cabin—and even then I did neither with much enthusiasm.

NOT ON THE BOARD

The Elements of My Queer Memoir:

- My life has been lived within shifting political histories;

- My home is located on an ever-looping map between my given and my chosen families;

- Femme lesbians are curio cabinets of misplaced heteronormative expectation;

- I hate the conflation of women and beauty, but secretly love when you tell me I’m pretty;

- Queer femmes resist tidy stories about our bodies to avoid confinement inside the stories others tell us about our bodies;

- Sex will always be on my pages;

- Queer friendship has always been my liberation;

- If I am now normal then I have changed normal.

And the self-redefinition at the center of memoir? In the 30th anniversary edition of The Word is Out they re-interviewed the beehive blond, still sitting aside her hubby, both of them in lawn chairs this time, great grandmothers now. She’s still high femme, but wears her bleached blond hair unbound and long. Time is change with echoes. Perhaps my placard will be just an image, a take-no-shit, old-school femme from the high hair days, not anyone in particular, just an enduring bottle-blond fortress, holding against against the elements, no plot, no redemption, more poem than story, swaying, never toppling.

Barrie Jean Borich is the author of Body Geographic, winner of a Lambda Literary Award in memoir, and My Lesbian Husband, recipient of a Stonewall Book Award in nonfiction. She's an associate professor at DePaul University in Chicago where she edits Slag Glass City, a journal of urban essay arts.