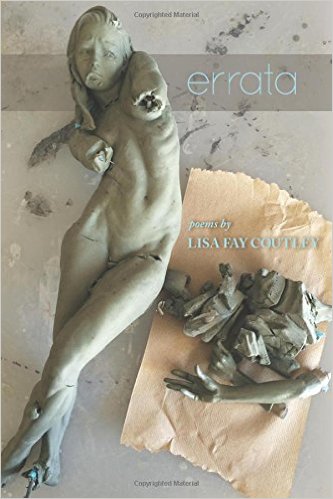

“Here is a dying we can all embrace”: A Review of Lisa Fay Coutley's Errata

When we feel empty, a natural tendency is to seek distraction—to fill ourselves with anything. But what can be gained from turning inward to face the emptiness directly? The Tao Te Ching speaks of emptiness as a virtue: the space inside the wheel that creates its structure, and the emptiness within a vessel that generates its purpose. Sylvia Plath conceived her own feeling of emptiness as “the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.” Errata, by Lisa Fay Coutley, takes a similarly cyclonic path through the hullabaloo of haunting memories and their daily reminders. Here Coutley addresses emptiness as it radiates outwardly in the different roles the speaker has inexorably found herself playing: a daughter, a vessel, a mother of two teenage boys.

The speech here is at once at once honest, brave, loud, careful, pained, and beautiful—weary, but never truly desperate. Craft-wise, Coutley’s words bleed into each other smoothly, with bold and deliberate line breaks and tight, striking language. But that’s not to say these are easy poems to read. They find the suffocating futility in everyday experiences and the painful thoughts and emotions that it’s taboo to admit to having: for example, about evidently untouchable joys like love and parenthood. Children are on their way to becoming parents, parents are either absent or dying, and pets are either dead or returned to the shelter. Inanimate objects absorb all of the disembodied discomfort of their surroundings, while people are defined by negatives, and spaces defined by absences.

Many of the poems focus on the speaker’s distress over her teenage sons: their dirty minds, short tempers, messy habits—

…one who cuts his meat into man-sized bites with a butter knife & gags at every meal.

—What roles will they too find themselves in, suddenly, someday? What vessels will they knock off the counter on their destructive march into the future? As a male reader of this collection, I felt a sense of guilt for having taken my mother for granted. To a teenage boy, a mother is a special kind of other: her thoughts and emotions seem to exist only as a gate which may be opened or closed for him; the mother herself, of course, remains in a constant state of contentment and self-control. By presenting a mother who continues to struggle to reconcile her various roles, Coutley helped me see my own mother in a way that I had a hard time perceiving her before, and, by extension, I also saw myself in a new context. That’s no small feat to achieve in a book of poetry—especially intensely personal confessional poetry.

There’s an inherent risk in confessional poetry of coming across as self-absorbed or unrelatable, but Coutley avoids that by keeping the images clearly outlined and allowing the focus of the poems to move around between them and the speaker. In my favorite poem of the collection, “The Way the Plot,” the words tumble down upon themselves, shaping the objects in the poem and the emotional state of the speaker, and also more generally the process of thought and memories, which tend to come in a downward spiraling formation ending at the most painful places.

always unexpectedly the apple falls rotten from the top tier of the wire basket

dull thud dumb roll always while your back is turned & you’re spooling

noodles with the small clean fork. on any otherwise quiet day so it strikes you like a man

you loved silhouetted against a garage wall behind your bright headlights…

The only difficulty I had with this collection is the same the issue I have with everyday life: it’s relentless, and sometimes tiring as a result. Much like real life, Coutley makes no promises to us about the direction she’ll be taking, or that they’ll be any rest stops along the way. This could be either good or bad depending on your taste: I often had to impose my own breaks to recover afterso many stark and heavy moments one after another—but I believe this to be an effective constructional choice which fit the content. Coutley’s best poems here are aware of their heaviness and decidedly unapologetic about it.

In fact, the collection is perhaps weakest in the few moments when it does try to give us a place reorient ourselves. In her “Ode to the Bottle,” a poem that stands out in its material directness and simplicity, Coutley bookends the empty space within a bottle as the:

Vessel of every desperate letter lost between one time zone & another, sun- starched but never wet..

The poem moves on through the many different uses of a bottle, from makeout-game piece to holder of lightning bugs on a summer night, finally holding a sailboat “always full of wind, always going nowhere.” These are interesting considerations, but the focus is so clear and tangible that it seems like a departure from the voice of the other more personal poems in the collection, which, rather than peering into objects’ inherent signifiers, do the seemingly impossible by crafting materiality out of emotion.

In the titular poem, which leads the last quarter of the four-part collection, the speaker hints at a solution, a sort of realization of the work-in-progress nature of her life. Here emptiness is not only a reminder of what has been lost, but a space to gaze across and see oneself on the other side.

I haven’t sanded the road, won’t strut across town in my ballet slippers. Your shape in this bed is my shape. Erase my whole notes from your page.

The collection really draws itself together in this last part of the book, leaving with a sense of self-aware resignation which, following everything that came before it, feels strangely uplifting. In the arresting final poem, “For My First Dog,” Coutley breathes new meaning into the moment of returning a dog to the shelter:

I’ve rehearsed my whimper, tattered the tissue & balled it in my pocket so when I say that it just didn’t work & they take you back to a cage, the volunteers will think I’ve cried

What follows is a quietly optimistic moment where the speaker, weary of lamentations and of reliving painful figments of her past, finally sees a glimmer of herself. It’s as if she realizes that returning the dog is not a mark of failure on her part, but a reaffirmation of her own free will.

In this collection, Coutley reminds us that while we may not be able to change the material truths of the past, we are always able to crop and reframe them to suit each present moment. Most importantly, we must remember that every evidently discrete moment is actually held on either side by something else. Once something has been erased, whether it was a person, place, or memory, its shell always remains, suspended in place: the messy scarring process even after the cleanest excision.

Karl Schroeder writes, studies, teaches, edits, and gazes into the abyss in Marquette, Michigan.