Writers on Writing #69: Dan Roche

Beyondness

My dad joined the Navy at seventeen, did eight years, got out and worked in the steel mills of Youngstown, Ohio, for four years, and then rejoined the military, this time the Air Force, in which he spent the next twenty-two years. Somewhere along the line, he took a literature class. He took classes over the course of much of his military career, mostly ones on management or techniques of warfare, but now and then some liberal arts ones. I assume they were required for the bachelor’s degree toward which he was gradually working, and which he got when he was in his early fifties and I was in college myself.

In that lit class, he had to read a Hemingway story. It was one of the Nick Adams stories, which he referred to simply as “that Hemingway story,” as if Hemingway had written only one. Or he called it “this story I had to read.”

The story pissed him off for years. Decades. Well, let me be more exact. I don’t think my dad had any issue with the story itself. What he groused about every time the subject came up was the way his teacher insisted he interpret the story.

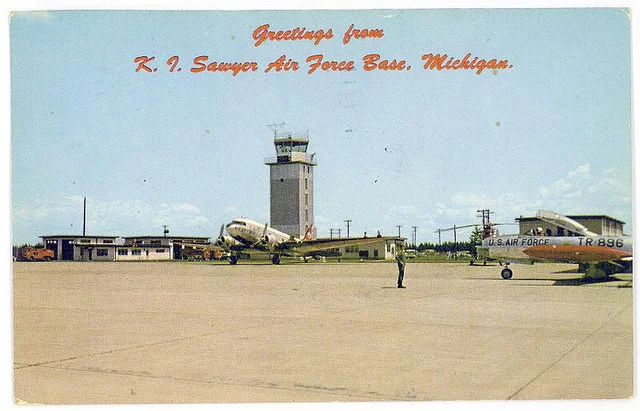

The story takes place in Michigan’s upper peninsula. I always thought that setting in itself would endear the story to my dad, because for eight years of my childhood he was stationed at Air Force bases in the UP, where he worked happily in the cold and snow taking care of B-52s. He had big, round, super-insulated boots and elbow-length mittens with leather palms and rabbit fur on the back and a thick, green hooded parka with his name in a blue stripe on the left chest. He liked the equipment of winter work. He and I used to take nighttime walks through the crunchy snow when it was fifteen below, and I would sometimes have to jog to keep up with his long strides. He would breathe in the frozen air deeply and proclaim how good the cold was. Stars hovered in the black sky. When I eventually read the Nick Adams stories—by which time I was living in the much less-invigorating landscape of southwestern Ohio—they filled me with nostalgia.

In the story, there is a forest fire. It’s destructive and terrifying. My dad’s teacher said that, sure, it was a forest fire in the upper peninsula of Michigan, but more importantly and interestingly, it was a metaphor for World War I. This interpretation did not sit well with my dad. What he said to me probably fifty or sixty times over the next thirty years was that the forest fire was a forest fire. Period. End of story. End of Hemingway. End of literary discussion.

Early on, I argued with him. Of course it was a metaphor, I said. I gave him some of my college-boy knowledge about Hemingway’s time as an ambulance driver in war-torn Italy, about how he was seriously wounded, about how war was his Big Subject. Forget it, my dad said.

My dad’s stubbornness surprised me partly because, for much of my childhood, he was the reader against whom I measured myself. He read fast and frequently. He liked history and thrillers. Leon Uris. Books about Ireland. He preferred the thick hardbacks, and he spent many, many hours lying on the couch with one of those books held open above his face. If it were a hot day, there might be a bottle of Coors on the floor next to him. It would usually take him only a day or two to finish a book. He’d stride through it as he strode through the cold Michigan nights.

And so, I never presumed—and still don’t presume—that my dad wasn’t a good reader, or that being able and willing to see metaphorical possibilities within a story might have been something he needed. He could see a metaphor when he wanted to. He just didn’t search them out or appear moved by the ones that crossed his path. Besides, he’d done two tours in Viet Nam—a direct experience with war which may very well have made him conclude that, for him if not for Hemingway, war wasn’t something you implied by way of a more confined horror.

I admired metaphors right from the start, even in the sports biographies and crime books I favored during my early teen years. Joseph Wambaugh’s The Onion Field attracted me as much by the question of what an onion field could symbolize as by the fact that the story told of a kidnapped Los Angeles police officer being shot to death in an actual onion field. I liked the mix of hard facts and figurative possibilities.

It took me a while to find a place where I could work with both.

***

At first, I went the route of solidity and job security: an undergrad major in mechanical engineering. I enjoyed the intellectual and pragmatic challenges offered by that profession, but the work left me mired in rigorous logic and hardnosed numbers, unable to imagine my way beyond the equations I sat at my desk solving. Though I was an adequate engineer, it became clearer each day I would never be a happy one. I missed words, thought about books, fixated enviously on that memory of my dad on the couch with the pages of a novel open above his face. I began taking night classes in writing and literature. During lunch hours and evenings, I read the stories of Flannery O’Connor, Russian novels, the poems of the Romantics. I discovered Keats’ idea that the secret to achievement is the capability “of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Reaching after fact and reason as an engineer, which is what I did all day, made me extremely irritable.

I left engineering as soon as I could swing it—for graduate school in English—but engineering didn’t instantly leave me. My first literature paper was on the poetry of Wallace Stevens. The professor scribbled only this at the bottom: “You seem to think that art must provide answers.” In her office the next day, she told me I might be happiest working in a library, where there were numbers and organized shelves.

I was convinced she’d misread me as badly as my dad was convinced his teacher had misread Hemingway.

I wanted to think more broadly, like a humanities major. How I’d learn that habit—especially since I was already in my mid-twenties—was unclear, though I began by throwing away all the pads of green graph paper I still had in stock, the kind on which I’d crunched so many numbers and circled so many definitive answers. I read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and saw, in Robert Pirsig’s explanation of the differences between the classical mode of thinking and the romantic mode, my own fractured life. Where I’d been and where I wanted to go.

Many times, I let myself feel despondent about having taken the wrong path and wanted to erase engineering from my memory completely. But in calmer moments, I did not want the habit of scientific logic gone from my life. It served me well: mapping trips, building bookshelves. I only wanted it not to be everything, or even primary. I wanted to merge what I had and what I wanted more to be.

That merging did not come in an epiphany. The very atoms of my being did not one day align in perfect balance. Over the course of a decade or so, however, I made progress. I’ve made more progress in the two decades after that.

One early catalyst was that professor’s pigeon-holing of me into a library job. Another came the very next term, in a nonfiction writing class that I signed up for not because I had any idea of what we’d do in there, but because the class would meet in a carpeted room furnished with a big circle of frumpy couches. The casualness of the room’s interior design proved liberating, as it was probably meant to. In that class, I discovered a form that let me anchor myself in facts and roam widely in imagination, questions, and unknowingness.

That sounds big. It actually took me a while—well beyond the end of that term—to limber myself up as an essayist, to get a feel for how to make the roaming really wide. In that class, though, I had my first modest success. It came in a short and true narrative I wrote about an odd early morning in a small Ohio town while I was waiting for a Greyhound bus. I was strolling the streets, wasting time. An opossum, which had maybe also been wasting time, was hunched in the vestibule of a sporting-goods store. When the owner came to unlock his door, he and the opossum had a stand-off. Neither knew what to do. People came by on their ways to work. Some commented. Others jumped toward the street when they saw the animal. I tossed the opossum some peanuts I’d bought for the bus ride. For half an hour, there was this funny disruption to the start of a workday. Then a no-nonsense guy came along, thought we were all pansies, and scooted the opossum away from the door with his boot. I ended the essay with the opossum sauntering “alone down the street, slowly, not confidently, but as if it had just come out of a movie and was trying to reorient itself to the real world.”

No answer, no moral. Just an image that enlarged the moment, if only slightly, beyond itself.

***

A rigorous study of music teaches you to think about the present and the future simultaneously. (You have to play the note you’re on, while looking ahead to the measures coming.) I’d make a similar claim about writing essays with rigor: that it teaches you to think simultaneously about the tangible and the intangible.

That combination is my aim as an essayist—in the same way, I think, poets aim to go further than the words themselves. Such “beyondness” is not my only joy in essay-writing. There are more frequent pleasures in the crafting of sentences and paragraphs; in the searching through my favorite book—the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus—for the exact and surprising word; in the cutting of phrases or passages that don’t earn their ways into a final draft. But it is the unforeseen and messy beyondness that interests me most as a writer.

***

I teach essay-writing as exploration, because I write essays myself as a way to explore. Explore what? I never know until I’m writing—usually along about the tenth or twelfth draft. Students don’t generally do ten or twelve drafts, which is part of the reason that my encouragements for them to break out of the linear and the bounded are met with initial (even lingering) resistance and confusion. For most of them, this is new territory. Their prior nonfiction writing has had to be formulaic and definitive: five-paragraph themes; argumentative essays; thesis and support; lab reports; or, as with my journalism students, facts, facts, and facts—with attributions. All necessary ways of writing, all appropriate to their times and places.

When we discuss any of their essays-in-progress, however, I always ask: “What is this about?” Their first-level answer is whatever’s named: a high-school prom, Grandpa’s cigar-smoking, a Michael Jackson song. Yes, I say, that’s the nominal subject, the thing named. That has to be vivid and clear and developed. You have to tell that story really well. And then I ask: “What else is the essay about?” At those moments, I am like my dad’s professor, wanting my students to imagine beyond the burned trees in order to see the Great War. Fairly often, they get pissed off.

And then they don’t. That might take weeks, months. We’ll do exercises to help. For example: Write two paragraphs about an incredibly famous movie line. (“May the Force be with you.” “You can’t handle the truth!”) But make your paragraphs about something besides the movie line. Start here, go there. Give yourself a subject that roots you, and a vision that lifts you.

Eventually—slowly, and then often dramatically—they begin to experience their writing’s potential for enlargement. They start to become essayists.

Beyondness in an essay—as in a poem or story—must be artistic and earned, and any leap should feel, to the reader, simultaneously surprising and inevitable. It’s an elusive combination.

Nor do the leaps always happen, or need to.

Perhaps, for instance, there is a straight-line relationship between my dad’s dismissal of a metaphoric reading of Hemingway’s story and my decision to devote myself to the uncertainty and ambiguity of essay-writing. I could use my old logic to reach that conclusion. It’s a fact that many times when I’ve been writing, I’ve been impelled into a broader questioning of my subject and my own experience simply by thinking of how my dad might stop at a certain point and say, “That’s that.”

Perhaps I write essays because my dad was the reader he was.

I could circle that answer and move on.

Or I could say that I don’t much believe in straight-line relationships, that such explanations don’t get at the many truths of a complicated story.

I’m sure, for instance, there is much I could investigate about why my dad’s literalness with Hemingway still frustrates me, though it’s been a decade or more since I heard him tell the same old story, and though he’s been dead for three years. Perhaps I could imagine how his reading of Hemingway was just as valid as the professor’s. Perhaps there are essays I need to write about how my dad and I diverged politically, religiously, socially.

If I take on that exploration, I’ll start with the facts. I’ll try to put on the page the tangible realities of him and of me and of us as father and son—the daily interactions, the conversations, the silences, the time I punched a hole in my bedroom door because I was infuriated with him, the times he stopped to let me catch up during those walks under the cold, black skies of northern Michigan. I’d want to recreate and dwell within all those immediacies, just as I’d hope that those tangibles would, somehow, lead me past themselves, if only a little bit, and that I’d be able, eventually, to discover what in this story is only itself and what could be—should be—more.

Dan Roche has published essays in Fourth Genre, River Teeth, The North American Review, Under the Sun, The Journal, and other places. His memoirs are Great Expectation: A Father’s Diary (Iowa 2008) and Love’s Labors: A Story of Marriage (Riverhead 1999). He was a 2005 fellow in nonfiction literature with the New York Foundation for the Arts, and he teaches nonfiction writing and journalism at Le Moyne College, in Syracuse, New York.