Alone with So Many Dead Things: A Review of The Desert Places by Matt Weinkam

1

At a friend’s fifteenth birthday party one autumn in high school, I played ghost in the graveyard with a group of guys. The party was on some uncle’s farm across the state line in Indiana, a ranch house out in the middle of a field with neighbors’ houses acres away on either side. Once we had cut cake and watched Colin unwrap gifts, once the sky had grown dark, we closed our eyes and chanted the pre-search one o’clock the ghost isn’t here... as the birthday boy slipped out into the yellowed corn stalks for us to come find him.

At the time I felt too old for the game, wishing instead for the kind of party that involved girls and alcohol, things I’d heard a lot about, things that at that age seemed both attractive and frightening. At twelve o’clock the ghost is here,I set out along one of the narrow rows alone, vowing silently to find new friends, older boys who were invited to unsupervised house parties, who weren’t afraid to break rules.

The sky clouded over, leaving little moonlight to guide the way. I tripped more than once on the hard dirt, feeling my way through the stalks until I came to a clearing. I stopped.

In the center of the field lay a pile of rusted farm implements: tractor, feeder, iron plow, some kind of rotary blade. There was a stack of broken pallets and plywood nearby and the whole freak show was in the process of being overtaken by knee-high grass and weeds. In the shadows at the edge of the mess was a twisted shape that could have been anything. It was the size of a man but bent and broken in such an inhuman way I couldn’t be sure if it was alive. I waited to see if it would move. This looked like a place where people died.

Looking back I wonder: Why did I approach? What pulled me toward that shape in the grass, lured me closer to the thing I feared rather than away from it? In movies, when someone ventures down into the darkened basement with no clear motive we attribute this to bad writing. But what motivates those of us who go see those same movies? What makes us sit in the dark with strangers for the express purpose of being scared shitless? In other words: Why is fear so damn attractive?

2

In 2011, Scholastic released a 30th anniversary edition of the children’s book series Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. This updated version was the same as the original and included the stories from all three Scary Story collections such as “The Big Toe,” “Oh Susanna” and “The Red Spot.” The only difference was the old Stephen Gammell nightmare-images of skulls, rotting bodies, and a streaking woman with spiders crawling out of her face had been replaced by the much safer and less frightening illustrations of Brett Helquist, best known for his work on A Series of Unfortunate Events.

It’s not hard to understand why Scholastic made this choice. Throughout the 1990s the Scary Stories books topped the list for most challenged books by the American Library Association, primarily due to the illustrations. More parents complained about these books than Heather Has Two Mommies or even Sex by Madonna.

Yet as soon as the new “kid-friendly” edition was announced and images leaked online there was a wave of backlash from adults who had been terrified of the books when they were kids. Articles began to appear online with titles like “Publishers Destroy Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark’s Amazing Artwork” and “Back in MY Day Horror Books Scared the Bejeesus Out of Us.” It seemed the parents who had originally worried over what their kids were reading had no idea just how much their children could handle. They were unaware of what kids really wanted.

I still remember my copy as a child, sitting on the bookshelf in my room where I could see it from my bed at night. Like many other kids, the book gave me nightmares. I would scream myself awake trying to get the spiders off my body. Of course I had books about dinosaurs and fire engines and a mustachioed man with a comical number of hats, but none of them occupied as much of my conscious and unconscious mind as Scary Stories with its cover image of a pipe-smoking skull growing from the earth. I pulled the book off the shelf and put it back again, opened to an image and then threw the book across the room, sat on my hands and dared myself to finish a story, to turn to the next page.

The book contained secrets my parents would never tell me. There were things in the world that didn’t fit into our neat suburban home. There was a darkness, an evil I could only learn about in those pages. I was frightened, yes, but I was learning something too.

3

It is time we talk about evil. To take it head on. In literature we go on endlessly about trauma and pain and heartbreak and fear and suffering and loss. We are attracted to the symptoms of evil, the effects, but have a difficult time staring down the beast itself. Few writers attempt to tackle the subject in more than a glancing way.

Save, of course, for our high priest on the subject, Cormac McCarthy, whose novels embrace the reality of evil like few before or since. Any reader familiar with Blood Meridian will no doubt recall the experience of living inside the blood-soaked darkness and dread of those pages. And there is certainly no greater villain in literature than Judge Holden, the embodiment of evil or at least its mouthpiece.

As disturbing as his novels are, however, McCarthy is still firmly a conventional realist. His characters may take on mythic statuses but they are grounded in reality. The trio of murderous fates in Outer Dark, for instance,is real in conversation but mythic in description. “They wore the same clothes, sat in the same attitudes, endowed with a dream’s redundancy. Like revenants that reoccur in lands laid waste with fever: spectral, palpable as stone.” He universalizes from the particular, rather than the other way around.

For good reason too. Because why, after all, would one want to take on evil directly as a character? Not Lucifer—like in Paradise Lost—but evil itself, the concept. Evil is abstract. One-dimensional. With a single, unwavering drive and goal. How would evil be tested? How would it grow or change? The question for a writer, and perhaps more importantly for a reader, is: how could evil be compelling character at all?

4

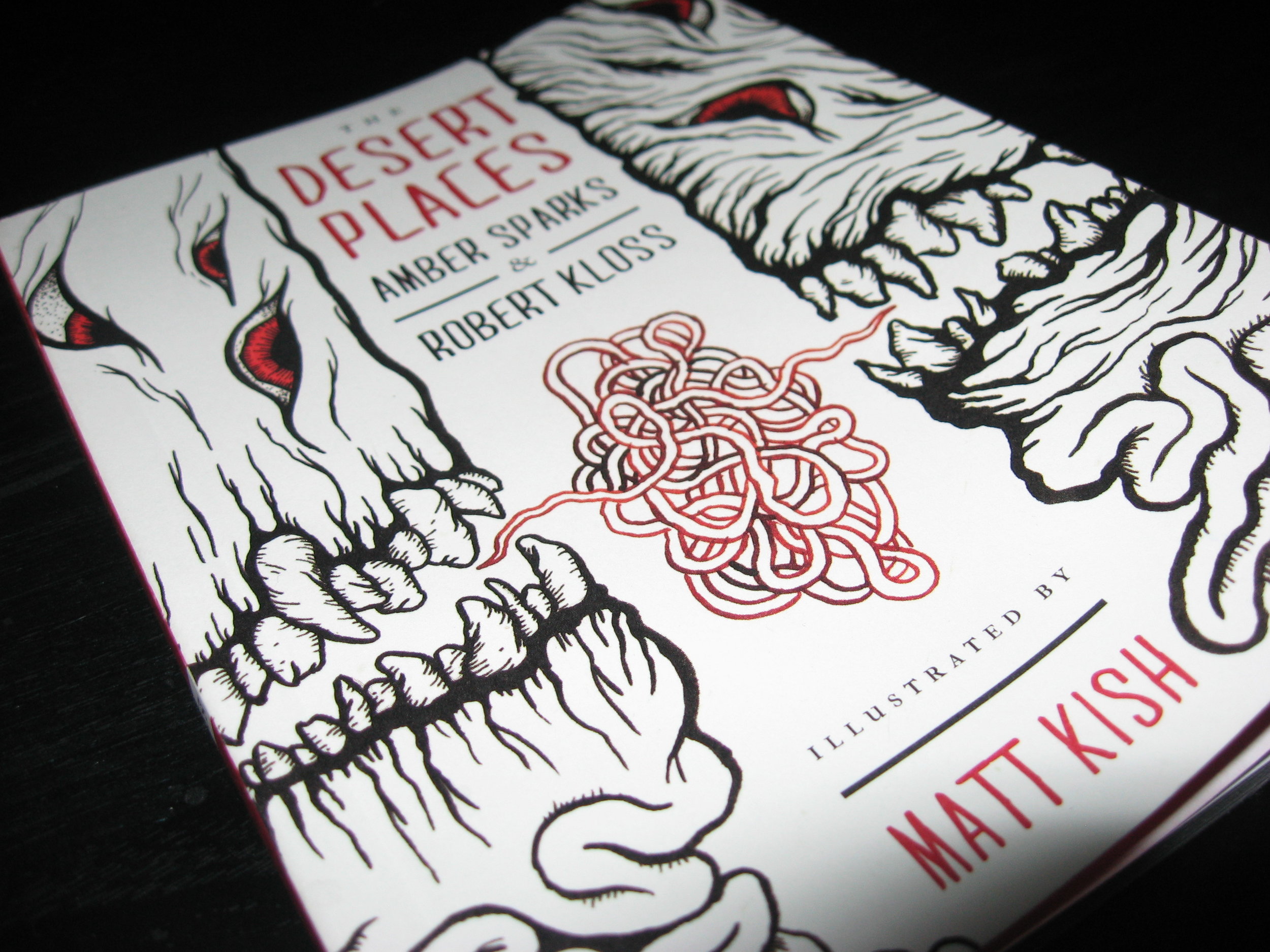

The Desert Places, a beautiful new pocket-sized hybrid novel co-written by Amber Sparks and Robert Kloss with illustrations by Matt Kish, begins rather appropriately with an epigram from Blood Meridian: “Those who travel desert places do indeed meet with creatures surpassing all description.”

What follows is a history of evil in ten parts, written in looping hypnotic prose, imagining those creatures surpassing all description from the beginning of time to the end and everything in between. Evil, in one form or another, is our main character, telling its story sometimes in first person, sometimes in second person, narrating destruction and cataloguing horrors both great and small. We see evil in the bloody battles in Colosseum of Rome, in the torture chambers of the inquisition, in the laboratories of enlightenment, at the beginning and end of humanity and beyond. No small task for such a small book.

Typically, the prose adopts a fire and brimstone stance, as in this passage from the third section, after the fall of man and before the rise of cities and civilizations:

And the drum-beats, the chants, as they called to me, as they touched their brows to the dust, as they painted their faces, as they wore the feathers of carrion birds as ornaments. As they split open young girls in my honor, as they tossed the offal to the flame. O hiss of blood and organ in the rise of smoke.

The description here of primitive ritual could just as easily apply to the text itself: drum-beat rhythm, chant-like repetition, the mixture of dust and paint that makes for a kind of dirty but beautiful lyricism. Sparks and Kloss don’t borrow from McCarthy’s style (they use commas after all) but put his vocabulary and “legion of horribles” theatricality to work directly on the mythic, the religious, the abstract. They particularize the universal.

Nowhere is this more apparent than the first section imagining primordial evil existing in the ether before the dawn of man. The chapter reads like a story from Calvino’s Cosmicomics, taking us back to an impossible time and asking us to experience what it might feel like to live there. Without any person, any thing, to latch onto, the writing floats around the subject with a series of questions:

Did you build the shape of man into the rocks to know the joy of murdering him? Did you ferment the first soil with the bones and bodies of your construction? Did you stack the lands with death even before the first life? And in the hours until the first victim staggered forth from the seas, did you wander the crimson lands, peer into the halls of death and mourn the vacant corridors? Did you tread the distant deeps and shout your name into that terrible emptiness? All the barren earth must have seemed a waiting cemetery.

The abstraction of evil in the abstraction of a lifeless pre-planet—there isn’t much to grab onto but atmosphere and mood. Yet by imagining particulars of soils and seas we’re also confronted with our own questions: What is evil without people? Does it exist independent of us? What would evil do in the emptiness of time before the formation of earth and life? And most interesting of all: would it feel lonely?

5

The Desert Places packs more than this ten-part history of evil, however. The book is full of extra sections such as images, inter-chapter lists, a prologue glossary, and an interlude. It is as though evil refused to be contained so neatly, as though it spilled over the boundaries.

By beginning with a glossary defining words such as power (“A great growing thing inside you. A white flash of want. A fever, a false prophet; a fall from perfect grace.”), Sparks and Kloss emphasize the role of language, place at the forefront as a kind of gateway to the evil within.

The lists that appear between chapters, titled [...an incomplete history of what passes for evil...], take ideas of evil from literature, history, philosophy, technology, and art as a way of showing just how familiar we already are with the idea of evil, where our concepts of evil come from, and just how endless they are...

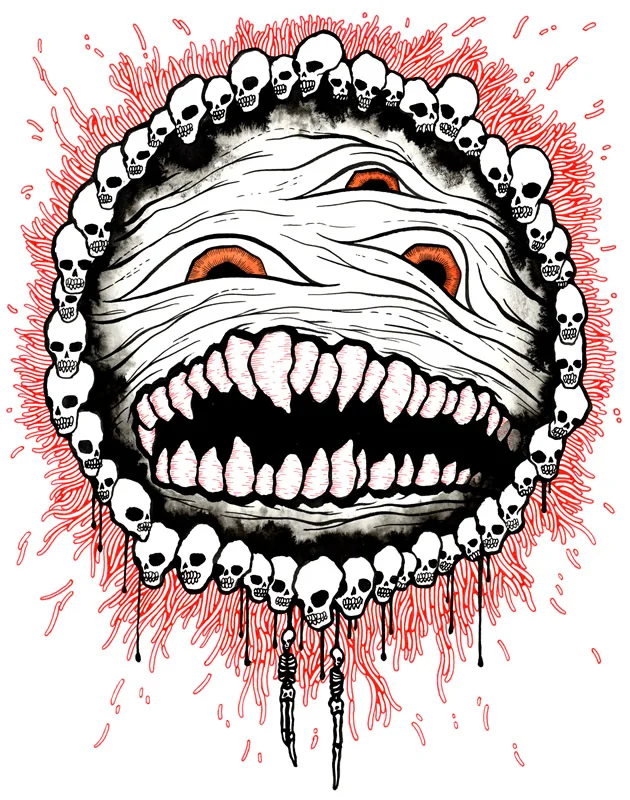

But more than anything else, it is the black and red images in the book that haunt us, that make it linger. Drawn by Matt Kish, illustrator of the stunning Moby-Dick in Pictures: One Drawing for Every Page, these images give the text an extra dimension. Nightmarish and intricately detailed. Overflowing with teeth, bones, skulls, and entrails. Though only occasionally representative of the chapter they are in, the images nonetheless function to embody this abstract concept and world. They are both hard to look at and hard not to look at. They invite and resist interpretation. Mostly, the images are just awesome.

In other words, this isn’t just a book but an object; the kind of text you want to own a physical copy of, to hold and touch and show off on your coffee table when friends come over. For such a small-sized bundle of paper it holds a great deal of power and attention. In bed at night I would watch it sitting there on my nightstand and return to a childlike state of fear and attraction, just like with Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. Only with The Desert Places that fear and attraction is amplified by the increased knowledge of and familiarity with evil that comes from being an adult, from watching the news, from witnessing history, from seeing evil deep inside yourself. There is still a fear of the unknown but the question is no longer what or how but why.

6

The trouble is about half way through the book, even a book as short as this, the subject matter and prose can begin to feel claustrophobic. The anaphora and circular rhythm of the language can become repetitive, the violence and gore can fail to shock from numbing overuse, and the singular character trait of evil ceases to surprise in any real way. A passage like this one, despite the skill on display, can lose its power when the whole book functions in the same mode:

They thrashed you with whips, with cat o’ nine tails, the metal studs lashing you to blood and ragged flesh and you told them the soul was a myth, a rumor, a breath of air only. They tied you to the wooden rack and stretched you until your arms pulled from your sockets and your vertebrae disassembled and you told them you had been witness to the birth of the universe and known the starts as they flickered into light and you said, “there was no voice in the void, no voice but mine.” They shut you in the iron device and close the doors, how the spike swung through your throat, your chest, you groin, and you laughed and gurgled blood and you said you would gladly recite every murder committed, every corpse devoured, every head smashed, every wife made a widow, every daughter made a meal, but you would not repent what had been as natural as breathing.

As Ben Marcus told Karen Russell, blue doesn’t stand out on blue. Without any contrast to violence, without any air in the prose, it’s easy to feel trapped while reading. The evil just seems dead on the page.

But just as the story is becoming too much to bare, Sparks and Kloss deliver a miraculous contrast chapter to let the air in. A counterpoint to everything that came before. It might be the best chapter in the book. After sixty pages of hellfire and bloodbath, our main character evil is suddenly, inexplicably doing to foxtrot in Cairo with a beautiful lady from Oxford.

The band is playing “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise” and a fat brunette is bungling the melody, slightly off-key. The champagne fountain is burbling down to a stream, your fellow dancers drunk or dazed, wandering off the floor in pairs. The stars are burning through the roof and you feel drunk, too, drunk with the past flooding through your veins tonight. You could murder her now, but sometimes it is hard to be alone with so many dead things. Sometimes you grow weary of death.

Evil, too, is trapped and exhausted. Evil, too, is lonely and end-of-the-night sad. The prose here is more open and playful, our central character gains depth and complexity, the capacity to surprise us again, to inspire something like empathy. And all at once the energy of the book is renewed, fresh and full of life amongst such death and destruction. Because the history of evil is the history of us, in all our failed humanity. This turn in the book is unlike any end-of-second-act shift I’ve read before. It’s something you have to read to believe.

7

Needless to say, The Desert Places is a rather grim book. But it is also a book full of frightening appeal. The quick 87 pages could be read in less than an hour but I suggest slowing down or spreading out the reading to get the full experience. I found myself taking breaks, making coffee, attempting to interact with other people in a normal human way before retuning to the darkness. The book gets inside your head in the best possible way. It can shift your perspective. In the same way that reading Blindness by José Saramago makes you re-appreciate the gift of sight, The Desert Places can make even the smallest act of kindness seem extraordinary. I can think of no better reason to pick up a copy than that.

Paging through the book for the second time late one night at a library coffee shop, I stopped reading to go order a drink. At the counter I found the eager smile of the cashier suspicious, diabolical even, and asked for a small green tea. I was still in The Desert Places, surrounded by death and blood and bone. It wasn’t until it was time to pay that I realized I didn’t have any money, I had left my wallet at home. I looked at the tea placed before me and back into the cashier’s eyes. I’m sorry, I said, I think I left my wallet at home. My body flinched, waiting for her wrath. It honestly felt like a moment of reckoning.

But then the man behind me spoke up. Don’t worry, he said, I’ve got it covered. Just add his order onto mine.

I looked at him. At his eyes and his teeth and the lines on his face. His small kindness was like an unknown shape on the grass before me, perhaps human but unrecognizably so. I wanted to approach it cautiously, with a certain degree of fear and attraction.

Thank you, I said. I could hear the surprise in my voice.

Don’t mention it, he said and he went out into the dark.

Matt Weinkam's work has appeared in TINGE Magazine, Monkeybicycle, and The Rumpus and he is an editor for Threadcount, an online journal of hybrid prose. He is currently in the MFA program at Northern Michigan University in Marquette, where he lives with his cat, Cricket, who is just the fattest.