Writers on Writing #45: Alexa Mergen

On Not Writing History

Over the course of many hot Henderson, Nevada, summers Helen told me stories as her arthritic hands, idled from stitching, held Western history books that she marked in places with folded Kleenex. My grandmother’s sharp memory recalled indignantly how her country cousins set her, a Salt Lake City girl, on a horse. She described her mother’s refusal of charity after she was widowed and how Helen, as eldest, was made to walk food baskets back to their Mormon donors.

Secrets obscured our family’s Mormon background. Helen’s grandfather, John Urie, was converted by missionaries. In 1853, he sailed from Scotland to America as a 19-year-old stowaway, eventually settling in Iron County, Utah, to blacksmith. He married twice, was widowed once, and wed 18-year-old Priscilla Klingensmith, as a plural wife when he was 39. Her father, Philip Klingensmith, a Pennsylvania Quaker who rose to leadership in the Mormon church after converting, became infamous for his part in the Mountain Meadows Massacre. On September 11, 1857, he and other Cedar City militiamen joined Paiute Indians to attack the Fancher-Baker wagon train which rested in the Mountain Meadows before crossing to California. At least 120 men and women, and children were slaughtered.

In eighth grade, I wrote a historical fiction about the massacre. My teacher evaluated the story as “useful,” gave it a “B” and commented, “This is worth doing over.” Ten summers later, Helen’s cousin, Anna Jean requested Urie’s journals, letters, and books. Anna Jean privately published two histories speculating Priscilla was an Arkansan, one of 17 small children spared, and that Klingensmith adopted her. Klingensmith’s deposition indicates he fired one shot, then set to gathering panicked babies and toddlers. (Urie rounded up the settlers’ livestock during the struggle.) Klingensmith’s son believed his father was shot on Mormon authority outside Caliente, Nevada, and left in a dry wash for testifying in court about the details of the crime, and for apostatizing. Before he died he warned his children “not to get too religious.” Before giving the documents to her cousin, Helen had me copy them, instructing me to write about this sketchy family past.

Over the next 20 years, I attempted memoirs and historical fictions that sputtered.

In September 2011, I dragged my husband and dogs on an impulsive trip to Cedar City, Utah, and Caliente and Panaca, Nevada. On the way, we passed a night along Highway 50. Sleepless, I watched the moon creep across the dark sky. Early morning, the dogs scented a herd of pronghorn moving like water across tan hills, and we watched them together.

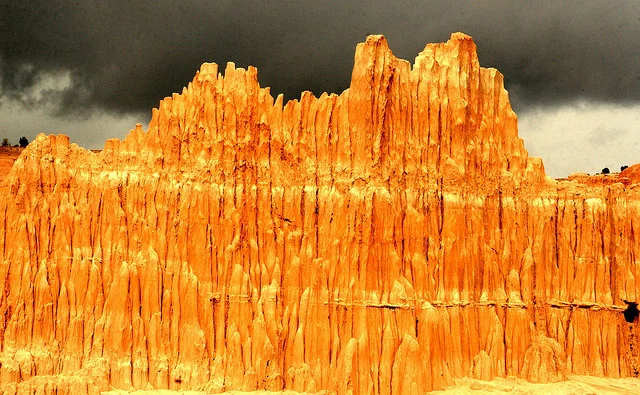

To a ranger in Cathedral Gorge, I revealed my Klingensmith lineage. Pain shadowed her face. The room stilled. Then she said the shame had been held too long. “I hope you find what you’re looking for,” she added, handing me a list of distant relatives, mostly Smiths, still living nearby. To conceal her identity, Priscilla signed her name Priscilla K. Smith Urie. “My grandmother told me to never mention any of it,” Helen emphasized to me.

In Cedar City, I read the inscriptions on tombstones. Across the street from the cemetery, at the Museum of Daughters of Utah Pioneers, I saw artifacts familiar to me from Helen’s house--shawls, photos, jewelry. We visited my great-aunt Mary, Helen’s last living sibling, recovering from a fall at a convalescent center. She wanted to get home to her ranch near Hamilton’s Fort, her weaving, her cats, the sheep, garden and open sky.

Matt and I passed an afternoon at the massacre site, sipping instant coffee boiled on our camp stove. We sat on grass under a temporary tent left over from a ceremony dedicating a new monument. Wind slapped at its white sides. Birds chattered in hills and flew through a reed-filled stream.

Like so many, Urie had stopped at Sutter’s Fort to work in California mines. When I returned to Sacramento from Utah, Urie’s voice landed on my paper as a flurry of poems. I wrote from September through February, set the bundle aside for six months, then took a peek. Many of the poems felt lonesome and hollow as iron pots lined up on museum shelves. The found poems though, composed from others’ writings, glimmered. And this one, from journals by Urie and his daughter Libby, Priscilla’s daughter and Helen’s mother, echoes.

Edict

Never turn a hungry person from your door or

refuse them a night’s lodging. In honor of Scots

let no one fall by the wayside. Keep yourself unspotted

from crimes & degradation of weak morals.

Contribute to the welfare of people. At last,

reconcile yourself to your reward,

to meet loved ones

who have gone before.

The poems are wrapped with string resting in a drawer. It’s time for ghosts to drift from red hills, to attend to what’s here, shored up by lessons recorded by the hands of those who lived and died with honor and in disgrace. It was a long time ago. This history is written on my bones. The secrets have been aired like linens on a clothesline in the sun, refolded with tissue paper, replaced in the cupboard, still.

In addition to poems and essays, Alexa Mergen writes fiction for adults and children. A list of her published work, as well as her performances and writing workshops, can be found at alexamergen.com.