Writers on Writing #38: Richard Hackler

On Writing Things that Not Very Many People Will Read

I was watching a friend sing at the bar the other night. This was a Wednesday. There are drink specials at this bar on Wednesdays, and the room was full of people: gentle, poncho-wearing undergrads standing in clusters, shouting at each other, waving their arms and spilling their beers and not really listening to my friend on stage, playing her keyboard, singing her songs.

I stood up front with a few other people so I could listen. My friend sang in a rich, overflowing voice, and she hunched her shoulders as she sang, and rolled her eyes, and wriggled her feet on the floor and moved her hands up and down the keyboard. People were finishing their second beers. People were getting drunk and talking louder to be heard over the music, and my friend shut her eyes and sang anyway.

Because my friend is one of those people—maybe you know one of these people, too—who exudes at all times a sunny nonchalance and seems to draw her happiness from whatever’s around her. She sings to herself when she walks down the sidewalk, and drags her fingers along trees and walls and railings, and when I run into her around town she meets my eyes and touches my arm and asks how I’m doing in a voice that shows she means it. This is my friend, and as I stood up front and nursed my beer and listened to her sing, I wondered if I might be falling in love.

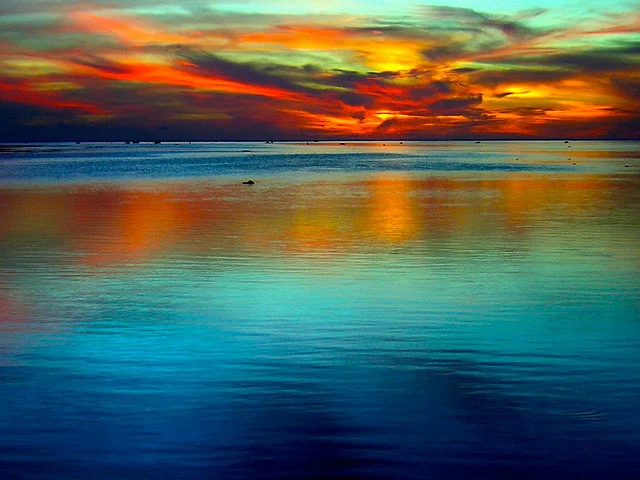

The next morning, I woke up early to attend a memorial service for a former student who’d killed herself. She was twenty-two. The service took place on the beach, and, afterward, I hung around by the lake and looked out at the waves and tried to pare my thoughts into something manageable.

I struggle with finding the motivation to write. For a while, I thought of writing only as a stay against loneliness. I wrote for people—I wrote essays to grow closer to friends or family. I wrote essays to women I was dating or wished that I were dating. I wrote essays and thought, maybe this will published, and a stranger will read it, and it will mean something to that stranger, and in that way the world will grow smaller and in that way we will both feel less alone.

But here’s the conclusion I’ve lately arrived at—the people in my life don’t really care if I write. They appreciate it when I dedicate the composition of creative nonfiction to them, but I don’t think they appreciate it more than if I just called them on the telephone. And, though I’ve published things in literary journals, I’ve yet to hear from strangers moved by my work. Because who reads literary journals. I barely even read literary journals.

So what’s the point? it has occurred to me to think, over and over and over.

I talk to my students about this sometimes. I teach composition courses, and my students are freshmen and sophomores, mostly. I ask them to think about why they’re in my class, and, beyond that, why they bother writing anything at all. And most of my students say back: we are in your course because it is required. Or: we chose you as a teacher because we have heard that you do not take attendance, and will grade our essays generously. But I always have a few budding English majors who tell me that writing, for them, for is an act of therapy. They tell me that they write to get their thoughts out of them, and that they don’t even know what their thoughts really are until they write them down. And they’re in my class because they want to become sharper and more articulate thinkers.

I tell these students that I admire them. Because writing has never seemed therapeutic to me. I’ve never kept a journal, and I don’t write anything when I’m upset. I know my thoughts already. I have to live with them all the time. Why would I want to write them out? They’ll still be in my head, only now they’ll also be on a piece of paper. This is what I’ve said to my students. But I’m beginning to understand what they mean.

That morning, when I looked out at the lake, I thought about my friend singing at the bar. She could’ve stayed home that night, and most of the people there wouldn’t have noticed or cared. She knew that. But she sang anyway. And you can go farther with this: most of the people in this town that night were in bed, and didn’t know there was music or drink specials at this bar, and most of the people in this state are only vaguely aware that this town exists—it is small, it is a six-hour drive from the state capital—and there are many maps of the United States that leave off our part of the country altogether. But my friend sang the same way she would’ve if a hundred people were listening, or a thousand, or if she were locked in a closet and singing to herself. She sang in spite of how small a thing it is to sing a song, in spite of how empty and sad the world sometimes seems. I’m stuck on this image—my friend moving her feet around on the floor, my friend’s hands pounding on her keyboard, my friend’s eyes fallen shut and her face coated in sweat—because I can’t think of a better answer to the ugliness of life than to bring your keyboard to the bar, to sing a song that no one will hear, to write a story that no one will read.

Richard Hackler is the nonfiction editor for Sundog Lit. He lives in Marquette, Michigan.