Everything Together All at Once by Tom Rich

I took up fencing in college. It was a great way to stay active, gave me some moderately interesting stories, and allowed me to strike other students with swords without getting in trouble. I also met my girlfriend there, so hey, added bonus. By my senior year, I was president of the club and helping to teach new members the very basic principles of fencing, like how to hold your weapon or where to put your feet. I got to wear a cool black jacket and everything.

One night, several weeks into a fall semester, I was reviewing how to do an advance, which is fencing talk for taking one step toward your opponent. “Ok,” I said, “so you want to make sure you're in a good en garde stance, keep your upper body still—back straight, foil in line, knees loose—and move your front foot forward, just a little, then draw your back foot up so you're right back how you started. Make sure your off hand is out of the way, too. Now just remember all of that while somebody's trying to poke you with a sword.”

Time after time, I ran into fencers who could do each movement fine in isolation: their advances and retreats were crisp, their bladework precise, their distance maintained. Yet when we finally got them to the point where they could actually fence, it all went out the window. Once they tried to put the pieces together, it all fell apart. Of course, I'm using the third person here when I should be using the first-plural: I can remember struggling with the same thing myself.

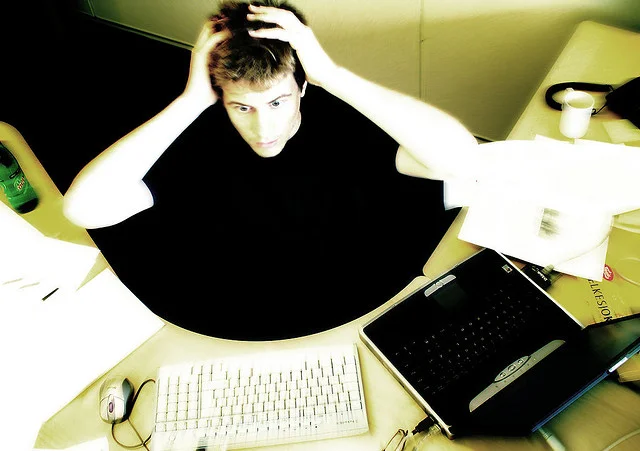

In writing, like in fencing, we're juggling a pile of different skills at once. Describing setting is a different trick than narrating action than illustrating character: they call on different clusters of memories and demand different things of the writer. Yet at the same time, if our stories are to have some sort of coherent wholeness to them, we have to consider everything together all at once. The setting has to reinforce character has to explain action. And that's assuming my breakdown here is even accurate, which it isn't. There's a lot to juggle while we write, and it certainly isn't easy.

And that's just within the story. Beyond its confines there are readers to consider, with all of their irritating habits. Too, I imagine most of us consider our own ultimate goals as writers, whether we want to amuse, entertain, instruct, educate, illustrate, demonstrate, obfuscate, or simply delight. It can be a bit overwhelming, and probably helps to explain the number of distractions we cultivate.

Fortunately for my analogy, those new fencers offer us a glimmer of hope. If they stuck around, and if they listened to their wise and witty instructor, eventually most had a match where things clicked: they maintained distance with their opponents, advance-lunged with a beat-disengage, and scored a touch (I wonder how many readers have Wikipedia's fencing article open at this point). After that it usually fell apart again, and we all kept working and having a good time, reviewing the pieces so they'd be better at each one when everything clicked again.

In writing, like fencing, everything clicks only every so often, and hopefully if you keep at it, and keep working on whichever pieces you can, the clicks come a little more frequently. May you never face anyone with a fast balestra, and happy writing!

Tom Rich is a writer, itinerant academic, and flannel enthusiast. His work has appeared in the Midwest Literary Magazine. Since graduating from Northern Michigan University in 2011, he has gone professional in filling out applications.