Writers on Writing #12: Tori Malcangio

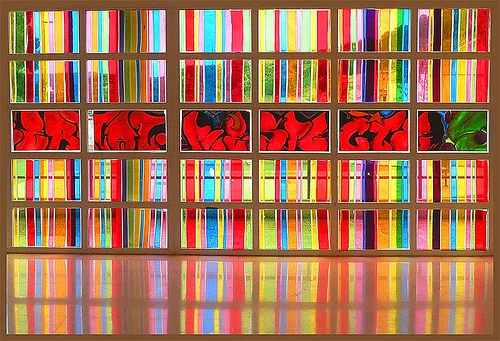

I remember Mom’s brief stint in stained glass: glass in every rainbow color spread across her worktable, long pliable tentacles of lead, jigs, glass breaking pliers, a soldering iron, and grinder. I remember asking her one afternoon what the glass would make and she said she didn’t know yet, she’d have to experiment with reflection until something moved her. Would I like to watch?

And so she moved pieces around, held up colors to sunlight until they bled into one another and began to make sense, not as pieces any more, but as parts: a leaf, a bird wing, a branch. She’d make cuts, shuffle positioning, make more cuts, hold the new shards to the sunlight, swap orange for red, green for purple, and eventually fuse with lead.

This is writing for me: a random process of reflection and matching opposing ideas until something totally unexpected emerges. A few times (almost none) I’ve ended up with Cathedral-grade glass art: a saint hoisting a lamb, a virgin swaddling her newborn. Most times I land in more foul territory: tragedy, family psychosis, hookers, housewives, husbands with hookers and psychosis. But the process is always the same, and never the same.

Here is my latest stained glass window (pieces scattered like buckshot in my brain):

Piece A. Yesterday’s horribly true story (and I start here, because like many story pieces or parts, it’s something I can’t shake and writing is merely my own default coping mechanism): A gorgeous 23-year-old model and fashion editor walks into a spinning airplane propeller and survives. The left side of her body is mangled, her prognosis is shaky. She’ll most likely lose her left eye. That’s the good news. I’m trying to imagine her life in the months to come and I‘m not sure if I should be allowed this intimacy. Her parents held her until the life-flight helicopter arrived, whispering over and over: I love you, I love you, I love you.

Piece B A five-year-old is pacing the house every morning upon waking, chewing holes in his dinosaur pajamas. He doesn’t want to go to preschool. He doesn’t want to eat breakfast. He doesn’t want to, in his words, go to school when Daddy is away, or on a Wednesday or when it’s raining, or with an itchy nose or to a place with sooooo many people. “This world is sooooo big, Mom. And my body is telling me to go kill birds and I don’t want to. Do you still love me?” And the mom lifts up her son and rocks him until she’s rocked herself out of the black, black hole. “I love you,” she says, “no matter what.”

Piece C A husband, away on business in Tokyo, accidently activates his Skype account, and oops dials his wife who witnesses his hotel room tryst real-time. She’s silent throughout, waiting for her moment, her grand gotcha. And just as he’s climaxing, she starts in. “Jason, Jason,” she yells. Stunned by the voice coming from the computer, he turns toward it. She waits for shock to impale him and says, in a tone at once forgiving and final: “I love you.”

And so I’m holding these pieces to light and starting to see their connective tissue, the parts of some bigger body. Shall we call it a page, a short story, a chapter, a pipe dream? I don’t know. What I do know is that an image of love at its most sacred and sacrificial is congealing and at some point—when the house is sleeping or my babysitter (the Patron Saint of freetime) arrives—the fusing will commence. I have no idea how the colors will reflect, or if the final body of glass will be worth a pause. Maybe. Maybe not. But I cut and grind anyway, and sometimes draw blood.

Tori Malcangio also pieced together A History of Heartbeats, our 2011 Waasmode Fiction Prize winning story.